By Louis Marvick

‘But how the devil did it come about in the first place,’ I asked, ‘that the conductor of a great symphony orchestra was demoted to the office of attendant in the monkey house at the zoo? That’s surely an unusual career move.’

I had to wait for Carstairs to light his pipe to hear his reply. Even then, what he said was not so much an answer as a reflection. ‘In neither capacity,’ said he, ‘was Bodo Sauerbier held in much affection by those under his authority.’

‘Nor did he like them,’ I countered. ‘That much was made clear at the inquest—by the human beings who attended, I mean. The whole viola section was ready to cut his throat, given the way he’d been riding them.’

‘The monkeys were equally furious,’ Carstairs agreed. ‘What a change from the man he had been thirty years before. Then, Bodo Sauerbier had nurtured the sprig of talent wherever it appeared. He had been open to the opinions of others—musical opinions—as deriving from the same source he sensed in himself.’ Carstairs shook his head. ‘All that changed with his lifetime appointment.’

I recalled the accounts in the press. While still the head of a many-headed instrument, Sauerbier had grown into an angry old man. He had not evolved with the times. There were women in the orchestra now, and persons of colour. Sauerbier was as indifferent to their feelings as a Roman tyrant to the feelings of a slave. He spoke his mind without fear of retaliation. He could not be threatened with the revelation of an ugly secret because he made no secret of his damnable opinions. His privileged position convinced him that he could flout the standards of decent behaviour with impunity.

‘He used to quote, as if it were the last word, Toscanini’s remark that an orchestra is not a democracy,’ Carstairs went on. ‘But the days when that was true were over. He did not realise that his baton had been officiously drained of its authority. The players were no longer suspended like puppets to be twitched according to his will. Above all, he was not supposed to strike with it, or even to make a striking gesture. He still tried to conduct emphatically, incisively, as he had done before the great egalitarian sea-change. But the orchestra’s response was milder, blander, softened by compromise. What they produced was a gentle consensus as to how the music should sound. That maddened him.’

Carstairs shook his head regretfully. ‘Do you remember how matters came to a head? The press played up the final scene with all the indignation of offended righteousness. With his cigars, his acid wit, his string of abandoned mistresses—all signs of his contempt for the rules that, in an advanced democracy, oblige us to defer to the feelings of others—Sauerbier had already cast himself in the role of a curmudgeon. One day, at an open-air concert in front of chattering picnickers, when his players, having supped on strawberries and fizzy wine in the interval, responded raggedly to a cue he had rehearsed with them a dozen times, he simply stopped. At first, no one was sure what had happened. No outburst announced his abdication. As the great beast lumbered to a muzzy climax, the horns puffing away with red, sweating faces, the violins slopping about, Sauerbier simply dropped his arms. The winds tooted in confusion, the strings sawed to a standstill, the whole band gave a creaking exhalation, the chattering picnickers fell silent. If only he had had a heart attack, the same act would have produced an effusion of sympathy. Everyone would have understood that the central pillar had been toppled by force majeure. But Sauerbier was in good health. He brought the temple crashing down on purpose. The players stared up at him, appalled, from the ruins of the edifice they had been building. You know what it was, I think? The “cathedral” section of Schumann’s Rhenish Symphony. Disgusted by their slipshod workmanship, Bodo Sauerbier had let it collapse like a house of cards.’

‘But surely he wasn’t dismissed for that!’ I protested.

‘No. The problem grew upon him gradually.’

To my annoyance, Carstairs now interrupted his narrative to fuss with his pipe. I soon forgave him, however, when I saw the abstracted frown on his face; for I realised that, as he tamped the cake of Sobranie in the bowl, studied the set of the shaft, and sucked on the stem to clear it of saliva, he was ordering his recollections with a view to presenting them as effectively as possible. At length, he took up the thread of his narrative again.

‘I’m thinking of that cynical Frenchman who observed that the faults of the mind, like those of the face, increase with age. The features of Bodo Sauerbier’s outward appearance that had made him the idol of concert-goers at thirty and forty—the patrician profile beneath the tossing mane of hair, the soft grey eyes with a light of hope in them, the expressive mouth—had hardened by seventy into something far less prepossessing. An arrogant glare had replaced the soft grey light; the hair had gone, except for some wisps quite yellow with age; the patrician nose had a veined and porous look, the mouth was turned down in grim brackets at the corners. In parallel with this outward ossification, the original defects of his character had grown more pronounced. He no longer respected the line between jocular ragging and outright derision. The butts of his satirical jabs were hard put to it to laugh along with the rest, and on occasion stood up, red-faced, and left the room. His vanity, too, got the better of his artistic conscience, as on the notorious occasion when he cut short a recording session so as not to miss a photo shoot. One might say simply that he became more brutal. His wit devolved to a blunt instrument of abuse. The gulf between the musical heavens he fashioned and the resentful crew under his baton grew wider, deeper; unbridgeable at last.’

‘I’m glad you remembered to mention those heavens,’ I broke in, ‘for there’s no denying that many people owe their most precious memories, their keenest feelings of musical delight to Bodo Sauerbier. Why, his understanding of the composer’s intentions was so acute that every other conductor’s effort to render them sounded like the clumsy groping of apes!’

I stopped short, arrested by the irony of what I had said. Apes, of course, are not monkeys, but pretty close. It was almost as if I had ‘channelled’ Sauerbier’s contempt for his musical inferiors. Carstairs’ wry smile showed that he took the point.

‘You are right, of course. No one who has not been in that supreme position can imagine the power that the conductor of a great symphony orchestra enjoys. With his plans laid out for him by the greatest geniuses, the worst he can do is to blur the creator’s idea. Penetrated by his sense of mission, proud of his unique fitness to grasp the quiddity of every score, Sauerbier grew ever more intolerant of bunglers. The difference between him and them acquired the magnitude of a difference between orders of creation—between branches of the evolutionary tree.’

‘So that’s it,’ I muttered.

‘Exactly. Remember your Burke? “Oh, what a heart must I have, to contemplate without emotion that elevation and that fall!” Damned he may be, but my heart still goes out to Bodo Sauerbier.’

We sat for a while in silence, contemplating the great man’s ruin. Then I asked, ‘What was the first time he went too far, do you recall?’

‘Oh, it might easily have been overlooked, so offhand was the rebuke, so trivial the occasion,’ Carstairs replied. ‘It was during a rehearsal of some twaddling piece by a new composer, Digby Piddlington-Smythe. Sauerbier was in general contemptuous of the ‘new music’ and resented the presence of a clause in his contract that obliged him to include samples of it in every season’s program. The pretentious effort by Piddlington-Smythe, however, with its pops and squeaks on dodecaphonic lines, its kitchen-sink orchestration and absurd title of “Experiment No. 3”, galled him particularly, and he was already in a bad mood when the rehearsal began. Yet he was nothing if not professional and devoted himself with perfect seriousness to unravelling the score. Then it happened. A tricky exchange between the bassoons and steam-whistle produced an effect so ludicrous as to make one member of the horn section turn to his fellow with a covert jeer. Sauerbier caught it.

‘“You two, Brasenose and Swinton,” he said sternly, raising his voice. “This is serious business. Stop monkeying around.”

‘A chill of scandalised offense came over the orchestra. Every trace of good humour vanished. As you know, in some cultures the worst insults are those in which human beings are compared to animals. In Persia, for instance, it is unforgivable to call a man’s father a camel. Such a comparison would seem merely quaint or exotic over here—as exotic as the camel itself. Dogs, of course, are another matter; their objectionable qualities are known everywhere. But what about monkeys, eh? What about monkeys?’

I bit my lip in appreciation of Carstairs’ point. Nothing could cut closer to home than to be compared to what one author called ‘that brutal parody of a human being’. We abhor our resemblance to our closest relatives in the scheme of creation, and loathe to discover a trace of the simian in the shape of our skull, the set of our eyes, the slope of our shoulders. In the range of insults, the subtle aspersion is more offensive than the blatant one.

‘And yet,’ Carstairs continued, ‘Sauerbier had only implied the comparison by his use of the verb. He had not called Brasenose and Swinton monkeys, but imputed to them a line of behaviour proper to that infraorder of primates. The measure was effective. Red-faced with embarrassment, the two addressed themselves to the work for which they were paid, and the entire orchestra, in sober mood, negotiated the intricacies of Piddlington-Smythe’s ridiculous score. On the whole, Sauerbier felt he had discovered an effective tool.

‘The next time he used the word, the butt of his abuse was not actually present, or even alive. I am not sure whether this was the result of calculation on Sauerbier’s part, or of chance; whether he was testing the waters of reception (so to speak) or simply did not care. The occasion was a detailed review of the Haas and Nowak editions of Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony. Only the principals of each section had been summoned to attend; they sat in uncomfortable chairs in a room appropriated for the purpose, gazing with feigned concentration at a large screen on which pages of the rival versions were projected side by side. This time, Sauerbier’s soul was wholly engaged. As you know, no work of genius has ever surpassed that penultimate masterpiece of Bruckner’s career. In terse, fragmentary bursts of language, pointing with a stick at the places where Haas and Nowak parted company, Sauerbier set forth his own theory of the great man’s intentions. He concluded by taking Haas’s side, adding, “Nowak did the best he could, but his version misses the spirit of the original. The trouble was, he had no imagination—the monkey.”

‘Just like that: casual, gratuitous; as if there were no question but that the epithet was right. Sauerbier gathered together his things, signalling that the meeting was over, and the principals stood up, glancing uneasily at one other. No one was prepared to challenge his use of the word; nor could Nowak, being dead and buried, take umbrage himself. The principal viola, who was standing nearest to Sauerbier, said afterwards that she detected a smile of satisfaction on his lips as he left the room.’

I could well understand the unease that Sauerbier’s remark had aroused. He had called Dr Leopold Nowak—a distinguished musicologist who was not even present to speak in his own behalf, or to refute, by fisticuffs if need be, the insulting appellation—a monkey. What was more, his offhand delivery implied that no hardening of nerve had been required of him as a precondition for slandering the late authority. He had taken the step without apparent hesitation, as if it were of no moment but a matter of course; and that unconcern, that disregard of the respect due to a man of Nowak’s attainments, stirred the misgivings of his auditors, none of whom could tell to whom their chief might next apply the scurrilous epithet.

As if he had divined my train of thought, Carstairs said, ‘Over the following weeks Sauerbier used the word only in connection with third persons. That was a relief to those who feared he might aim it at themselves. His loathing of contemporary “singer-songwriters”, for example, prompted him to refer to them as “monkeys thumping on banjos”, even though banjos were not actually involved in their activity. At the same time, he took to aggravating each minor scandal by affixing an ugly adjective to the noun, thus darkening the verbal stain. One occasion stands out in everyone’s memory. It was on the morning after a deeply searching performance of Brahms’ First Symphony. Sauerbier had bought the “quality” paper and, having settled himself under a NO SMOKING sign in the loges, was enjoying a matutinal cigar while leafing through the Arts section, looking for the review. The players were setting up their stands, moistening their reeds, rosining their bows and generally warming up for the day’s rehearsal with much burbling and tooting flecked by virtuoso runs. All of a sudden the cheerful noise subsided, like the twittering of birds at the approach of a human being. A vibration of concentrated anger seemed to fill the air, emanating from Sauerbier. Then, in the ominous silence, a muttered word or two was heard, that no one could understand, followed by more silence as he read further, rattling the clenched pages; and finally it came, in a shocking, sputtering roar, the outburst that everyone had dreaded, polluting the air they breathed, laying waste to decency in its gross release:

‘ “The d—–d, f–th-sh—–g monkey! How dare he! So! The distinguished music critic of the [here he named the rag] takes it upon himself to condescend to Brahms, does he? Correcting the faulty taste of the public—is that what he thinks he’s doing? Why, the f–th-sh—–g monkey-f—-r should be castrated! Put to hard labour for the rest of his days! ‘Whipped with wire and stewed in lingering pickle’, as Cleopatra says!” In the half-darkness of the loge his face could be seen working with fury as he crushed the paper into a ball. Then, going slack, as if the current that thrilled his frame had been cut off, in an access of hopelessness he added, “What’s the point?” and let the paper drop to the floor.

‘There was no rehearsal that day. A subdued hubbub followed his departure. Then someone retrieved the crushed paper and opened it to the offending page.

‘The centre-piece of the evening was Brahms’ First Symphony [he read], an exceedingly erudite work containing details which betray an honest and profound musical thinker. But it lacks grand, sweeping ideas and is deficient in sensuous charm. The Allegretto is marked “grazioso”, yet it reminds one rather of the gambols of elephants than of a fairy dance, and, with its inordinate length, its total effect is wearisome. Brahms takes an essentially commonplace theme, gives it a strange air by dressing it up in the most elaborate and far-fetched harmonies, keeps his countenance severely, and finds that a good many wiseacres are ready to guarantee him as deep as Wagner. The fact is that his themes are dry, insipid, and of trifling importance. The fuss and fury of preparation leads to a weak performance, and a little mouse is the reward of a great groaning and sore travail. Of course, I am willing to admit that the Symphony is grand and impressive and all that. But it reminded me of a visit to a sawmill. Great logs of melodies are hauled up with superhuman power and noisily sawed into boards of phrases varying in length and thickness. Some of them are reduced to shingles and laths of figures, to be finally stacked away in a colossal pile of a climax. Yet how prosaic, how hopeless, how unfeeling, how arid a musician Brahms really was, a leviathan maunderer, a self-inflated mediocrity, like a great baby addicted to dressing himself up as Beethoven and making a prolonged and intolerable noise. The poor man had the brains of a third-rate village policeman.

‘Naturally, this review aroused a good deal of indignation, as well as some amusement, but no one saw anything in it to excuse Sauerbier’s grossly abusive language. True, the author had compared Brahms to an elephant, but that was surely fair play, in no way comparable to calling the author a monkey. Many of the players secretly shared his opinion. Brahms was so earnest, so emphatic, so lacking in the sense of what was “appropriate” in a modern liberal society, that a suspicion of fascism seemed to attach to him. There was something domineering about his music, something worlds away from (say) the light irony of Debussy, that everyone could approve. No wonder, then, that a petition was got up demanding that the orchestra’s board of directors rebuke Sauerbier for his outburst.’

(Here I must interrupt my transcription of Carstairs’ narrative to address a difficulty I have encountered in preparing it for publication. How, I asked myself, could I convey the full quality of Sauerbier’s abominable outburst without replicating the offense he gave when he made it? To write out his words in full would certainly do that, while at the other extreme, the pungency of his language would not transpire through a decorous paraphrase, and the verbal act that drove him to his eventual doom would not be understood. I thought of completely replacing the words with dashes and referring the reader to an appendix where they could be read, or not, à volonté, thereby accommodating one reader’s fastidiousness and another’s appetite for violent meats. But I judged that that solution, too, was unsatisfactory, inasmuch as it would amount to throwing an enticing veil over the horrors and ensure, contrary to my wish, that innocent minds were corrupted. To obviate that danger, I thought of replacing the words in the appendix with dashes as well; but that would merely have been to offer a link between two mysteries. A further expedient, suggested by Krafft-Ebing’s procedure in his notorious compendium of perversions, would have been to translate Sauerbier’s words into Latin, Greek, or Hebrew; to wrap them in a gauze of learning so opaque that none but a classical scholar could tell what they originally had been. But, since I am myself ignorant of those languages, I would have had to hire a translator to do the work, and must have taken the accuracy of his product on faith. How could I have judged whether his ancient Greek version, say, conveyed the pleonastic resonance that Sauerbier had achieved by attaching the noun ‘f—th’ to the participle ‘sh—–g’? How could I have judged whether a rendering in Hebrew or Latin of Sauerbier’s hideous invention, ‘monkey-f—-r’, did justice to his idea that the reviewer was not, perhaps, a monkey himself but someone who had congress with monkeys? I could not. I should have had to hire a second translator to vet the work of the first, without being able to tell which translator’s opinion to prefer. The compromise I have adopted will undoubtedly disappoint both those who are willing to confront Sauerbier’s words in all their original ugliness and those who cannot bring themselves to entertain so much as a hint of the execrations that burst from his mouth; yet it offers a middle way out of the difficulty—one that, I hope, will satisfy the general run of readers as well as the publisher of this account. In any case, it is the best I can do.)

‘Sauerbier’s behaviour did not improve,’ Carstairs went on. ‘The throngs that flocked—or should I say the flocks that thronged—to his concerts paid the directors’ salaries, so it was no surprise when the expected rebuke turned out to be a slap on the wrist. The female members of the orchestra, who had already formed a caucus to work for gender equality, were dismayed by the spectacle of their chief triumphing in the rout of his examiners, and sent in their own expression of “concern” at his “inappropriate language”; yet the reward of their effort, I am sorry to say, was to hear themselves derided as “hand-wringing snivel-b—–s” from the podium, and to watch Sauerbier roar with laughter as he set fire to their letter with the tip of his cigar.’

‘He never!’ I exclaimed.

‘I am afraid he did,’ said Carstairs, shaking his head sadly. ‘From then on, he became even more reckless, more indifferent to the proprieties, more openly scornful of the feelings of others, flinging the word “monkey” about as if it were a synonym for “person”. The musicians were not defeated, however. They took the failure of their campaign to eject him as a temporary setback and set about mustering their forces for a second attempt. If only there had not been a mole, or rather a rat, in their midst! But there was: Teófilo Dandini, the oboist. He was the closest thing that Sauerbier had to a friend. Small and dark, with eyebrows that he twirled up at the corners into tiny horns, he played his instrument with such dexterity that the conductor had never had occasion to scold him, and sometimes, after Dandini had negotiated a particularly difficult passage, beamed at him with genial approval. The little man basked in the good opinion of so terrible a judge, and conversely, when one or another of his colleagues fell under the scourge, his dark eyes sparkled with malicious delight. Having caught wind of the plot to depose his patron, he went to see him in his dressing-room immediately after the next concert.

‘The great man had removed his formal attire and sat before his dressing table on an incongruous gilded stool that looked too fragile to bear his weight. He was removing makeup from his face with a cotton swab. A white sheet depended loosely from his shoulders, offering the unappetising spectacle of his sagging, hairy chest to Dandini’s view. A mixture of sweat, patchouli and witch hazel struck the oboist’s nostrils, and he hesitated to enter.

‘ “Ah, Teófilo, my friend! Come in! Good job in ‘Le Tombeau de Couperin’, by the way! That’s a tricky bit of work.”

‘Dandini squirmed with pride for a moment, then coughed meaningly and broached the topic of his errand. Sauerbier laughed.

‘ “What can the monkeys do?” he asked. “My tenure is for life. I’ll say whatever I damn well please! The monkeys will just have to take it.”

‘Dandini did not join in his chief’s amusement. “They’re planning to invoke the ‘moral turpitude’ clause,” he warned. “Every contract has one, and tenure is no defence. They’ve hired a trendy psychologist to testify that your words are ‘deeply hurtful’ and that your intention is to deprive them of self-respect. If they can get the judge to see it that way, you’re out.’

‘Sauerbier’s laughter dwindled to a feeble chuckle as he considered this. Dandini waited patiently, and in the meantime noticed that the conductor was wearing high-heeled bedroom slippers, evidently part of his lounge attire. Each slipper was adorned with a pink ostrich feather, and together they made a shocking contrast with his bare, hairy legs. Dandini averted his eyes.

‘ “I take your point,” said Sauerbier slowly. “What do you suggest?”

‘ “I’ve thought of something that may confound them completely,” Dandini said, “while preserving for you the satisfaction of telling them exactly what you think of them. How would it be,” he went on, approaching his point with sly relish, and sidling up to his superior so his suggestion seemed to slip into his ear, “if you simply substituted the words ‘human being’ for ‘monkey’? No one could object to that; yet you would know, and they must infer from earlier experience, what you really meant. There might be a good deal of amusement to be had in such a substitution. You could use the words obliquely—to refer offhand, for instance, to ‘those human beings in the viola section who keep fudging their sixteenth notes’—or with devastating bluntness, directly to an offender’s face: ‘You, sir, are a complete and utter human being. I suggest you go home and work on the passage you botched today as if your job depended on it—which it does.’ ”

‘ “Not bad, not bad!” admitted Sauerbier, stroking his chin. “It really amounts to inverting the tenor and vehicle of the metaphor, doesn’t it? Yes . . . yes! I can see where that might be amusing. Dandini, my friend, I am indebted to you! I’ll put your idea into practice first thing tomorrow.”

‘And so he did. The next concert was to begin with that old chestnut, the “Tannhäuser” overture, a piece which affords plenty of opportunities to screw up. Especially for the strings, the long accumulation of enharmonic demisemiquavers in the final pages is difficult to play in time and in tune. The first rehearsal was barely under way before Sauerbier stopped, pursed his lips as though he had tasted something nasty, leaned towards the second violins and said: “Excuse me, but . . . do I understand correctly that you consider yourselves musicians? Really? Strange! Having just listened to you play (if one can call it that) I should have taken you for human beings. Yes, you heard me right—I called you human beings! That’s what you sounded like, and that’s what you are!”

‘Here Bodo Sauerbier broke off into what might be called insane cackling, so delighted was he with the success of his stratagem. The second violins knew exactly what he meant. They burned with resentment, but there was nothing they could say, for they were, in fact, human beings. Avoiding each other’s eyes, they applied themselves again to the difficult section, and this time they got it right.

‘Before you give vent to the same feelings of indignation I felt when I learned this,’ Carstairs warned, seeing that I had risen from my chair and was pacing up and down in great agitation, preparatory to denouncing the brutal lack of regard for other people’s feelings, the hateful self-complacency and sheer bad manners of the scoundrel, ‘let me assure you that Sauerbier’s triumph was short-lived. The problem was, he could not refrain from piling insulting adjectives onto the noun. Had he contented himself with calling people human beings, he might have persisted in his career of disrespect indefinitely. But it wasn’t long before he began to embellish the phrase with adjectives that could not be encrypted without losing all their expletive force. The licence he gave to that impulse was his undoing. The principal violist recorded one of his outbursts on her Handy, and the authorities, when they heard it, were forced to act.

‘The judge in Sauerbier’s case was a very enlightened individual, or collection of individuals, whose preferred pronouns were they, them, theirs. Trained in a tradition that treats penal measures as means of reforming the culprit, rather than as instruments of revenge, they struck upon the clever idea of ordering Sauerbier to do community service among the creatures whose name he had misused so freely. That’s how he came to find himself translated, almost overnight, from the head of a great orchestra to an attendant in the monkey house at the zoo.’

Carstairs had now answered the question I had put to him some 4,680 words before. I now understood how Sauerbier had come to be demoted; but I was still ignorant of the steps that had led to his sticky end in the monkey house. Luckily, Carstairs was well informed on that topic, too.

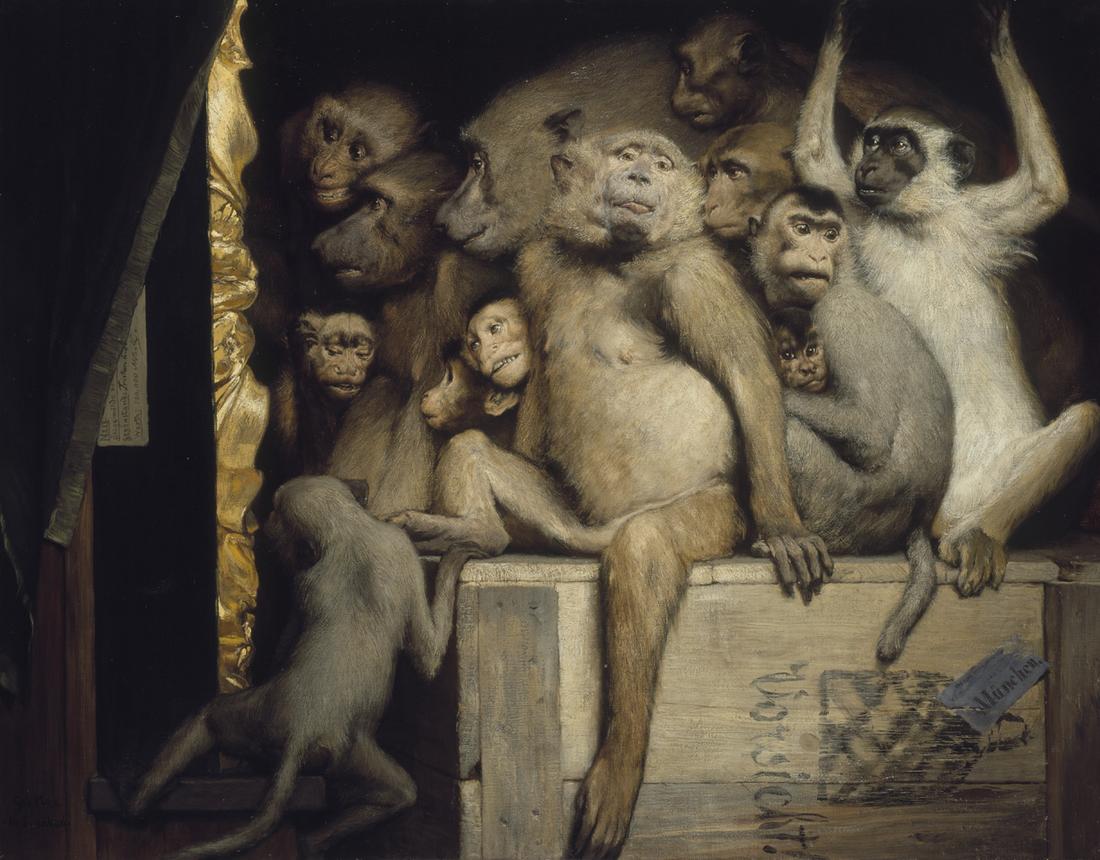

‘Picture to yourself the disgraced conductor showing up for his first day of work. Instead of the elegant silk jumper he had worn to rehearsals, he was clad in a suit of scruffy bleu de travail. The observant capuchins recognised it as the uniform that Sauerbier had inherited from a former employee: their sharp eyes caught sight of burn-marks on the sleeves left by ash from the last man’s Gauloise, and their keen sense of smell detected the trace of black Algerian tobacco beneath the reek of Sauerbier’s flowery after-shave. A shriek of triumphant derision went up from their cage, and within moments, all the other denizens of the house knew that a new human being had been given over to them. From the pigmy marmosets at one extreme to the great strapping mandrills at the other, by way of the gibbons, gorillas, chimpanzees and bonobos, not to mention the macaques and orangutans, an indescribable clamour arose, a true cacophony of grunts, squeals, bellows and chest-thumping, all laced with the intelligible message of bestial satisfaction, of savage joy in the possession of a new plaything.

‘Even Sauerbier’s arrogance was shaken by the hostility of his reception. His legs shook, and he groped for the chair on which he had been told he might sit at intervals. The hellish din still beat about his ears, and he sank his head in his hands, digesting the fact of his damnation. A half-chewed banana landed at his feet; he looked up to find the rufous gibbon that had flung it at him clinging to the bars of its cage, gloating eagerly as it waited for his reaction. The creature was possessed by the same spirit of heartless curiosity that children exhibit when they taunt the monkeys in the zoo. “ ‘As flies to wanton boys . . .’ ” Sauerbier groaned; and picked up his bucket. It was time to slop out the cages.’

‘I’m surprised he submitted to his punishment so tamely,’ I remarked. ‘With all his faults, Sauerbier was a man of spirit.’

‘Ah,’ replied Carstairs, ‘that’s where the judge—the judges, I mean—showed their ingenuity. They anticipated that he would not embrace the wholesome spirit that informed their sentence. Does an alcoholic willingly accept a glass of warm milk in place of his tipple? So they added a back-up measure and made sure he felt its teeth. If he refused to carry out his duties in the monkey house, Sauerbier would instead be sent to live among very old people who would drag him down with them into the grave.’

‘Good Lord!’

‘Yes. One can hardly imagine a worse fate,’ Carstairs shuddered. ‘So, much to the monkeys’ surprise, the new attendant quietly bore all the fruits and insults they hurled at him. He went stoically about his business, harried by screeches, battered by mangoes and coconuts, bullied by the occasional marmoset that sprang onto his back and pulled his ears. For almost a week, the prospect of slow death in an old folks’ home kept his resentment in check.’

‘But it didn’t last?’ I hazarded.

‘No. Sauerbier brooded on the egg of his hatred. Oh, there was a moment when he might have changed course. One day, while cleaning out the cages, he noticed that one of the orangutans did not participate in the campaign of abuse that the others mounted against him. It was an elderly female with greying hair and drooping dugs and a melancholy expression on her face. She seemed to shrink back when the others bared their teeth and gums at him, and shuffled away into a corner to escape their spiteful chittering, looking at him over her shoulder with what would have been taken for sympathy in a human being. Sauerbier was annoyed to find that he was touched. A sign on the cage gave her name as Maggie and her age as nineteen. That was almost the same as his age, measured in orangutan years. He realised that he tended to look for her when he passed by on his rounds, and that, when he found her, their eyes sometimes met. At other times, however, she was so lost in thought that she didn’t look up, and then he stood for a moment at the bars, studying the ungainly way she rubbed a dusty thumb across her forefinger.

‘On the whole, however, his mood grew darker and his thoughts turned to revenge. The spider monkeys were particularly hard on him, and before long he took to dragging his metal coffee-cup across the bars of their cage, taunting them with his relative freedom of movement, goading them to spit and snarl in paroxysms of frustration. “So! You people don’t like me, eh?” he laughed, swaggering up and down and aping them by sticking out his tongue and scratching the top of his head. The chimpanzees, who until then had been less determined in their antagonism than the representatives of other species, were enraged to see him tease and mock their cousins, and put their intelligent heads together in a counsel of war. Of course, the suspicion was never proved, but it was almost certainly they who orchestrated the brilliant operation that resulted in Sauerbier’s death. Why, the cage has not been built that a chimpanzee cannot find his or her way out of, if he or she puts his or her mind to it! All that is known for certain is that, one morning a month after taking up his new appointment, Sauerbier did not open the doors of the monkey house at the usual hour. The director of the zoo, who held the only other key, was summoned, and when the doors were thrown open, Sauerbier’s lifeless body was discovered on the floor. An eerie silence reigned in the house, and all the apes and monkeys looked on, po-faced, as the corpse was dragged away.’

Carstairs had reached the end of his tale, and stood up to go. I suggested we meet again the following day to smoke, swig port and chat. ‘Can’t be done, I’m afraid,’ he said regretfully. ‘Been transferred to Paris; start there tomorrow. Going to live among the frogs.’

Be First to Comment