by Jeffrey Meyers

Jim, my greatly admired friend, taught at Berkeley and was the brilliant biographer of Thomas Mann. I’d reviewed his earlier volumes; and when I left teaching and moved back to northern California, I looked him up and we immediately hit it off. He was twenty years older than me, a benevolent father figure, and I was honored when he asked me to edit some of his essays. The bulky bearlike man, who had poor eyesight and moved slowly, surprised me by saying he’s once been an expert ballroom dancer. There were strange guests at his luncheons: a Bulgarian theorist, Reagan’s speechwriter, an old friend of mine now lapsed into silence and ventriloquized by his talkative young wife, a professor who’d crushed me in grad school and now grudgingly praised my work.

It took me some time to appreciate the truly awful qualities of Jim’s French wife. Simone was angry and bitter about everything: her exile, her career, her lack of recognition, her daughters, her disease—even her life in America. She was furious about her family’s forced exile from France in the 1930s when she was ten years old. Still, they escaped unharmed and had sufficient money to settle comfortably in Montreal, and she eventually earned a doctorate in chemistry at McGill.

I had another French-Jewish friend, Berenice, whose experience was infinitely more traumatic and tragic than Simone’s, but who turned out quite differently. As a child, she actually saw her Polish-born parents screaming “we are French citizens” as they were arrested by the Vichy police and destined for an extermination camp. Their neighbors in the Paris courtyard, indifferent or hostile, merely watched. She was brought up by her brother, well educated in a Rothschild-sponsored school, married an American army doctor and lives happily in California.

Simone published a few scientific papers and did some part-time teaching. But she felt, with some justification, that she had sacrificed her career for her husband and daughters, and did not get sufficient recognition for helping Jim with the research and editing of his books. She forcefully told me, with displaced wish-fulfillment, that my wife—who also gave me considerable help but did not write my books—should be listed as co-author on the title page.

Simone hoped her daughters’ achievements would compensate for her failures and frustrations, but they also disappointed her. She thought her younger daughter should have been given a teaching job at Princeton, though she’d published nothing more than an introduction to someone else’s book and her successful rival had written several important works. This daughter was married to a prominent professor, whom I thought was an intellectual fraud. Simone had enthusiastically praised him, but when he dumped his wife for a young student, Simone insisted she’d always known he was a pretentious phony. Right after Simone, in an unusually affectionate moment, told me, “you are a dear friend, just like family,” her older daughter called long-distance from Paris. They immediately got into a hot dispute, she slammed down the phone, and I felt that being part of her family was hazardous. Though politically liberal, she also quarreled with her best friend, who was fanatically Left-wing.

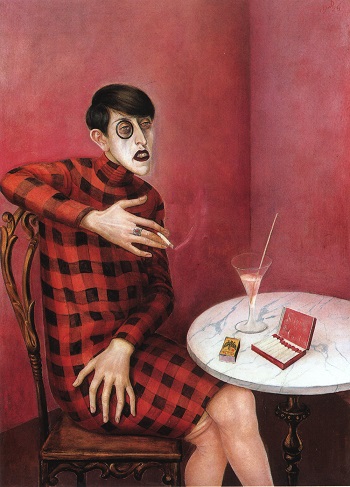

Once pretty and petite, Simone had lost her looks and got shriveled up, but was still vain. Small, thin, nervous and birdlike, she had a prune-wrinkled face. When I had to greet her with the requisite French two-cheeked kiss, my lips felt the deep grooves in her cold, cold-creamed face. She had suffered from breast cancer and had not come to terms with that or anything else. She was still understandably outraged by the need to wear a lopsided wig after radiation treatments and by the cruel removal of her breasts in surgery.

Edgy and irritable, contradictory and critical, opinionated and dogmatic, especially when she was ignorant and vulnerable, she would justify her dislike of Indian food by incorrectly insisting, “they put cumin in everything.” Eager to dominate the conversation and oblivious to the feelings of other people, she never let anything or anyone escape her sharp eye and wicked tongue. Terribly snobbish about her French background, she believed Canada was better than America, France was better than Canada. She thought Yale (where Jim had previously taught) was superior to Berkeley, Sorbonne superior to Yale. She’d dated, before her marriage, a French professor at Yale, but felt obliged to assure me that she’d remained chaste and “didn’t sleep with him.” She would have seemed more French, and more human, if she had been seduced.

Simone was also an intellectual snob. She despised women who took pride in cooking and housekeeping, which she thought were incompatible with the life of the mind. (Uneducated women who did such menial jobs were beneath contempt.) On one occasion she was exasperated when the kitchen light bulb was shot. I said, “come on, let’s change it,” got a chair and replaced the bulb. She’s always thought an intellectual should not stoop to such menial tasks. But now she was awed, saw my usefulness and praised my efficient performance.

She was a perfunctory and neglectful hostess, and though proud of French cuisine, was a terrible cook. She once hurled a green cloud of parsley, which she forgot to put into the stew, right across the table. When her dishwasher broke down, the greasy silverware slipped out of my fingers and had to be secretly wiped off before I could continue the meal. She had a flat in Paris but resolutely refused to look up my Paris-poet-friend and his French wife, who was disqualified by being an excellent cook.

My wife spent a lot of time preparing elaborate meals for our weekly meetings. Simone, who drove their car, started coming late and leaving early to see other friends near us in Palo Alto. For once, I lost my temper. I told her that I found her rudeness, treating us like a fast-food counter, very irritating. She felt I was needling her, covered her embarrassment with self-assertion and bit back: “Are you telling me when to come and when to go?” “I’m telling you there won’t be any more lunches at our house. From now on we’ll meet in restaurants.”

Her rudeness persisted to the very end. I said goodbye to Jim on his deathbed. At his memorial service I was asked to speak, after a break, as we moved outside in the sunny weather. The moderator told everyone to assemble and sit down, but Simone, standing in the back, continued to talk to a friend and ignored my speech. Afterwards, she tested my patience by provocatively asking me to repeat what I had said. I published a memoir of Jim in the alumni magazine, quoting letters he’d sent me while they were on summer holidays in France. Instead of thanking me for the affectionate memoir, she insultingly claimed that Jim had never sent me any letters and that I had made them up.

I loathed Simone and could easily have crushed her assertions, but put up with her for twenty-five years. She’d interrupt Jim’s stories and say, “I heard it before,” and he’d bravely insist, “then you’ll hear it again.” But she looked after him and smoothed his ruffled hair, and they were happily married. I was devoted to Jim, and loved our lively and stimulating conversations. His kindly character and intellectual brilliance made it possible for me to restrain my short temper and adopt an unusually mild and tolerant persona.

Jeffrey Meyers, FRSL, has had 33 of his 54 books translated into fourteen languages and seven alphabets, and published on six continents. His latest work is Resurrections: Authors, Heroes—and a Spy.

Be First to Comment