A week before December 10, 2015, when the Salman Hit and Run case was about to be heard in the Mumbai High court, Anand, my best friend Jhanavi’s husband, called me frantically, asking me to come to the Gymkhana grounds in Hyderabad, as soon as possible. I cancelled my assignments at hand and reached there as soon as I could. I couldn’t believe what I saw. Jhanavi was sitting under a makeshift canopy. It was the Shamiana, the blue canopy which most South Indian families used for a celebration in the verandah space of their homes. Her family was with her. Apparently, Jhanavi had bullied her kids into making huge signs with “Acquit Salman” written in black ink. They were holding them begrudgingly. Every once in a while they would look at Anand and then at me, wanting to leave. Anand was looking like a scared cat caught between his wife and his kids.

Anand had said something about Jhanavi calling the local news channel and arranging their coverage of her. How she had done all that she wouldn’t reveal. I could see a few local channels descending on the grounds with their cameramen and news anchors in tow. After what she felt was enough press, Jhanavi announced to the news channels her ‘cause’, her commitment to Salman Khan of Bollywood, and her agitation here in Hyderabad for the star of Mumbai.

After a million questions the majority of the press left. One particular news channel did not leave entirely. Two men wearing their reporter tags were left at the canopy. When we dissuaded her from eating or drinking anything because it would look bad for her reputation, she protested. “But, but I just said fast – I didn’t say I will not eat food or drink water. Who said that?”

After a while she said to herself, “That’s ok I guess! These two will be gone by night. Who has really seen me after that?” Her idea was to fill herself up in the dark and pretend to be fasting as soon as morning came.

But those newsmen never went away. They continued to report Jhanavi’s activities back to their studio throughout the night. We could hear them talking on their cell phones behind the canopy. Jhanavi tried to leave once in her car, citing a change of clothes. When she saw that one newsman called up his counterpart in the studio and was reporting her movements, she quietly sat down. Once when she tried to go to the bathroom, one newsman followed her all the way to the door darting glances at her handbag and the bathroom for evidence of cheating. Exasperated, Jhanavi opened her bag, shoved it in his face and said, “There is nothing here, look. I am just going to the bathroom, will you let me go now?”

This continued for the next three days. The reporters were rotating every twelve hours with the outgoing ones briefing the incoming ones on Jhanavi’s movements. Just the timing of Jhanavi’s fast, a week before his Hit and Run case in high court did the trick. Her fast started trending all over the country. Unable to handle the onslaught of enquiries, the news channel, which had the far sightedness to post round the clock newsmen, started a new 24-hour channel called “Trending News.” During the inauguration ceremony their CEO said that it would stream all the trending news on the social media; it would become a voice for the netizens of India.

Jhanavi’s story was the opening show on “Trending News.” When she slept, when she sneezed, when she woke up, when she lay down, was soon a point of discussion in the country and for those Indians living away from the country. As Jhanavi became the “Trending News,” I remembered how it all started.

***

It was the fall of 2015. I was in India for an extended six-month stay for my book signings and promotional tours. Jhanavi and I had been friends since the time we were roommates getting our master’s at Louisiana Tech University way back in 2000. Even after ten years of working in an American firm, when her husband, Anand still had not managed to obtain his US Permanent Residency because of a ‘fire’ at his lawyers’ offices, they had decided to return home to India in 2005. They had built their lives in Hyderabad. After the birth of her three children, Jhanavi had quit her daytime job, saying she was unable to balance all the aspects of life. She had chosen to become a homemaker instead.

I had stayed on in the US to become a writer. Since my hometown was also Hyderabad, I would often visit her during my trips home. She would keep me apprised of Hyderabad news and I would tell her of the life abroad. Our bonds were deep enough to transcend the physical distance. We had managed to stay in touch through child rearing, home owning, and parental deaths. Now, in her mid-fifties, Jhanavi had developed a sense of emptiness. Her teenage daughters and son were becoming busier with their activities.

She took to calling me almost every other day during my six-month trip. I had decided to help her by listening to her every word and give her my time no matter my schedule.

“But I do want to do something drastic in life, I am tired of living this mediocre middle class life where everything is compromised,” she cried one day.

“Every mediocrity is celebrated. No one strives for excellence. Everything is ‘ok.’ Nothing can be done. Every bad decision is because of the fault in stars. Every good decision is not individual triumph but lady luck shining. My kids don’t even listen to me. For that matter no one, including my husband, seems to give me more than ten minutes of their time. I am fed up of being a nobody.”

She felt she had deviated from her path of wanting a thriving career when she chose to become a fulltime mother and a wife. If only she had stuck to her original plan, maybe life would have been different. Maybe she would have saved the world and received applause. After three kids, and a million compromises with life, she was losing it. She wanted to be a world famous figure, fast.

“I think I know what I will do,” she declared to me. “I will fast until death like the Iron lady, Sharmila Chanu from Manipur.”

“Oh! You mean the lady in North East India who has been fasting almost her entire life to lift the Arms Act?” I asked.

“Yes, that’s the one I am talking about,” replied Jhanavi.

“But I don’t understand, Jhanavi,” I said. “On the one hand you want more out of your life and on the other you want to end it all. I don’t understand your dichotomy.”

“Well, that’s the whole point, isn’t it? My whole adult life I have felt unappreciated by both family and friends. My intelligence has been disrespected; I have felt underutilized at work. When I switched from being a career woman to a homemaker I thought Anand would recognize my sacrifice. Instead all he praises me for these days is for something I cooked or when the house is kept clean. Neither he nor my kids have time for me. The four of them, all they talk about constantly, is how to become the next big thing of India, how to start an ecommerce business or an IT firm or how to become an actress. What about me? I don’t want to die like this. I too want to be known. I want to become so famous that all these people who ignore me now will feel sorry for doing so,”

“Ok, but what will be your cause?” I asked.

“Cause?” She sounded as if she had heard the word for the very first time. “Hmm! Do I need to have a cause? Why can’t I just fast? Like Gandhiji used to, every now and then?”

“But, Gandhiji had a cause–once it was the salt Satyagraha, another time it was the Quit India and another, the usage of only Indian clothes. He fasted at every step of the country’s freedom struggle for a particular cause. What will be your cause?” I prodded her.

“Cause! Cause! Cause! Hmm! Let me think.” She gave a pause as if she were thinking. “How about this, honor killing? Remember the journalist, Nirupama Pathak, who was killed for loving a lower caste boy? That will be my cause.”

“So you will fast for what, for the girl or for speedy judicial process? How will you prove that you were affected directly because of that incident? There is already a court case running on it, you know, right?”

“Hmmm! Yeah! I see your point,” Jhanavi said. “It will lead to more side tracking than necessary. What about that schoolgirl, Ruchika Girhotra, who committed suicide because of the police commissioner of Haryana? Remember? It was in the news.”

I replied that I did not have an idea about the case as I had not followed that news.

“Oh! I will brief you. You know, the girl was molested and when her family decided to file a complaint, she was hounded so much by the Haryana police commissioner and his cronies that she ended her life while her case was still ongoing. It’s unbelievable how much her father and younger brother were harassed even after her death. Ruchika’s friend, who witnessed her molestation, has been fighting on behalf of Ruchika for many years now. Nothing has been proven in court. After a wait of nineteen years, because of the slow Indian judicial process, the police commissioner was given a sentence of a mere six months in jail. I was so angry at the time of the court verdict. I will fast for her.”

“Since her friend is already fighting for it, why don’t you go contact her? Ask her how you can help,” I suggested.

“Hmm! Ok! But I have my family here in Hyderabad na! Now when I think of it, Haryana seems so far away.”

It was incredible to hear her excuses. She wanted to be someone, wanted her life to be worthy enough, yet she did not want to leave the comfort of her home.

“I will think of something else,” she concluded. “But I will find something, fast until death, and become India-wide famous and ultimately world famous, you will see.” She ended our call abruptly.

Jhanavi called me back a week later.

“Hey! I know my cause!” she said excitedly. “I will fast for the Narmada Bachao Andolan.”

“But activist Medha Patkar is the very face for it,” I reminded her. “What leverage will you get in the presence of a stalwart like her? And what is it that you are fighting for? Do you know?”

“Well, hasn’t it something to do with the Narmada River getting polluted?” she asked.

“Forget it!” I said and ended the call. I was exasperated with her for not knowing that the Narmada Bachao Andolan was about the displacement of villages due to the construction of a dam on the River Narmada and not about the river getting polluted.

The following day when she called again, I said I was rushing to a conference with my publishers and had no time to chat when she interrupted me, “No, don’t end the call,” she said, still mad that I had ended our previous call abruptly. “Don’t underestimate me, I will fast for trees, like the Chipko movement. I will hug a tree so tight, as if I was glued to it, like the original protestors had done in the Himalayan foothills in the1970s. I will inspire everyone in Hyderabad to hug more trees, and as a result, the culling will stop and the city will become green like it used to be decades ago. Even you will agree that it is a worthy enough cause, won’t you?”

I wished that she could see the rolling of my eyes. “Ha!” I said, “Go find a tree first.”

“Fine, I will,” she said and ended the call. She called me back in an hour. In an urgent tone she said, “There are no trees left to fight for! Malls have replaced all the trees! What do I do?” she cried. There was genuine panic in her voice. It seemed like her goal was slowly slipping away.

A month passed where she did not mention the fasting project. I thought that maybe she had given up the idea. I did not bring it up because I did not want to embarrass her. One day I was in her house visiting her family and we were discussing the separation of the Telangana state. She suddenly gasped, “You know what? I just had an idea! I will fast for separate Ameerpet!” she shouted.

“What?” I almost dropped the teacup in my hand, “What do you mean separate Ameerpet?”

“Ya! Separate Ameerpet. Wasn’t it Potti Sriramulu’s fast that got us a separate statehood for Andhra? Didn’t KCR do the same thing recently? Don’t we have a Telangana state because of that?”

“Let me get this right,” I spoke cautiously. “Separate Ameerpet! Not separate Andhra, or Telangana, or Hyderabad even, but a separate Ameerpet, a separate state for an area in the city of Hyderabad? Is that correct?” I asked.

“Ya! Ya! You heard it right,” she said, “I am talking about ‘a separate’ Ameerpet.”

“What is your concern? Why do you think you need a separate Ameerpet?”

“Well,” she said, “I have lived my entire childhood in Ameerpet. I used to shop extensively in the Chandana Brothers there. I went to school and college there. My favorite religious temple is still there. Yet, I feel Ameerpet is being sidelined in favor of the new airport area. Ameerpet has not been represented appropriately in favor of the juggernaut called ‘Hitec City’. When we moved to Hyderabad, I had expressed my wish to settle down in Ameerpet but Anand wouldn’t agree. He said it would be very tough for him to drive all the way to Hitec City for work. That is the reason why we live here now, in this Hitec City, so far away from my parents. I go there once in a while but not as much as I would like. And when I visit, it takes me forever to just walk to my favorite temple. Time was when I used to walk all the way from Ameerpet to Sanjeeva Reddy Nagar in my school days. Now it has become an impossible task. Nobody has bothered about improving the traffic congestion in Ameerpet even though it had generated revenue for so many years, much before Hitec City became the famous IT hub of Hyderabad.” She was moving her body and looking at her husband in a certain way, using her hyper-pitched teenage voice as she said that last sentence.

“I mean look at the famous Durga temple of Ameerpet,” she said, standing up and using her normal voice. “There is the temple and its tree in the middle of the four road cross section. There is heavy vehicular traffic—the cross-country trucks, the bicycles, the motorbikes, cars, and the three-wheeled autos going both ways on either side of the temple. I don’t blame them. For the people who live in the by lanes or further down from Ameerpet, this is the main path. Then there is the public transportation that has a couple of bus stops built along this way so that their buses, whenever they come, almost bring the entire traffic to a standstill. I have never seen a single traffic constable being posted here. Yet there is more than one present in the other busy intersections of the city.

“The vegetable, flower, and fruit vendors, the poor guys who pile their stuff on four- wheeled carts, stand in that traffic to sell their wares. Then there are the clothes shops along the street on both sides of this same four road cross section. For someone like me who has been used to do her shopping here all through childhood, it’s impossible not to cross the street and look at the clothes. You know, my dear mother when she was alive fell down in the middle of the traffic, once on a shopping trip with me, because she couldn’t judge an oncoming two-wheeler as she was crossing the street. Luckily she wasn’t injured. I mean, just look at the temple right in the middle of all this chaos! I bet one of these days the goddess’ hand will change her posture. Instead of her usual reassuring pose she will hold her breath, like this, from pollution!” She demonstrated by closing her nose with her right hand.

“It is all a sign of neglect for my beloved Ameerpet, the same Ameerpet which was the first revenue generator for Hyderabad before the so called ‘malls’ opened up,” she continued. “If I were to be made the chief minister of Ameerpet, which I will be, since I will be the one fasting, I will construct a ramp around the temple, not over it because our religion does not permit, but around it, for traffic. The cloth merchants can continue to sell in their shops below. Only autos, taxis, and two-wheelers will be allowed on the ramp. The ramp will go around the temple and become a parallel road to the main path after a certain distance. There will be no parking on the ramp. There will be one drop off location and one pick up location so that people can be dropped off and picked up. The vegetable, fruit and flower vendors, the ones who cannot afford real estate, can sell their wares in wired baskets around the temple on the ramp. The ramp will be wide enough to hold the vendors, the visitors, and the vehicles. Only a specific number of vendors will be allowed. Two elevators will be constructed to take people up to the ramp and down again. When it comes down, the elevator will open near the entrance of the temple. That way the traffic, the vegetable vendors, the shopkeepers, and the temple can all coexist peacefully. All they need to do is make me the chief minister, which I bet they will, because most vendors in Ameerpet know me anyway.”

She played with this idea for a week. When I visited her next, I saw huge paper posters of “Separate Ameerpet” in her room. When I questioned Anand, he simply shrugged his shoulders. When she found no help from her family or from me, she let go of this ‘cause’ too.

***

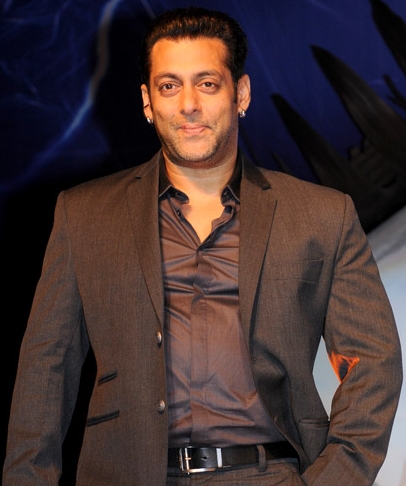

Jhanavi called a week later. “I will fast so that the film star Salman gets punished. Look at him, shameless guy. A homeless person is killed, a black buck is poached, but no one gets punished.”

“Yes, so what?”

“Doesn’t young Rashi want to be in movies? And wasn’t she saying that the easiest way was to move to Mumbai, impress Salman, and grab a movie with him? Did you think about her future? Anyway, what good is that to the society in general? Will the dead person’s family be paid any money? Will wildlife poaching stop? He will be back in less than the jail time.”

“Rashi with Salman? Is she serious? No way. Film actress in my family? Is that a good idea? What do you think? ”

“What’s wrong, as long as she ends up like Priyanka Chopra and not Sheryln Chopra?”

“Hmmm! You are right. My daughter Rashi Rao aka Priya, um, I can get used to that!”

I didn’t hear from her for another three weeks. “Hey! I think I know,” she called me in the middle of the night.

“Hey, you know what?” she said. “I will fast so that Salman is acquitted. Isn’t it cruel of the Indian government to keep two cases still open on him when he is proving he is much bigger than that?”

“Like what?”

“Well, recently he organized a fashion show for humanity, isn’t that enough? I mean how many celebrities really walk for humanity. He gave Katrina’s family a great gift by establishing her as the actress, and recently didn’t he comment that he was happy about his ex girlfriend(s) and that he had no bitter feelings in him? Wow! What a role model! He also said he was not actually directly involved in those two incidents, they were unfortunately committed by somebody else, so he shouldn’t be prosecuted. Poor guy, the government should leave him alone.”

“But how is he doing any social service?”

“Well, he tweeted about an old actress and how she was being evicted out of her house unfairly. Didn’t he? Didn’t he?” She pressed me for a response.

“And he is such a sweetheart,” she continued, when I didn’t react to her. “He made sure Sonakshi Sinha ate less and worked more and eventually gave her a movie role. Tomorrow he will do it for our daughter, for other daughters, for all the daughters of India; we really need a man like Salman in the film industry— who gives a break to ‘needy’ girls. A progressive man who believes in women’s freedom. I like him. Most importantly by not marrying he is helping in the population cause. I have decided. I will fast for Salman. Somebody must help him. I will.” She gave us an ultimatum.

I expected her to drop this one too just as she had dropped her past ‘causes.’

***

When Salman was acquitted on December 10, Jhanavi’s joy knew no bounds. She was sure she was going to be in the spotlight. A newsman whispered that Salman was going to make a visit to her after all. Her daughter and son seemed suddenly involved and more interested in mummy. They stopped going to their college and began sitting beside her. Even Anand had stopped making “work” excuses. Finally some respite, she thought. She hollered to her husband— “No lime juice, please bring some soup. Is Sambhar allowed instead? I am a South Indian, I should be given Sambhar instead of the lame lime juice.”

To Jhanavi’s joy Salman did visit her in the middle of the night a few days after his acquittal. It felt like the entire Hyderabad had descended on Gymkhana grounds. The entire ground was resplendent with the glare of camera lights. Rashi was desperate to get into the cameras beside him. She brought out an album of her pictures and shoved it in his hand. After everyone took a million selfies with the Salman, his secretary sought the soup to wrap up the frenzy quickly. Salman’s time was precious. He had to complete his unfinished movies that had to be stalled because of the court case. Soup in one hand, as he was about to feed Jhanavi, a media man asked him whether he would now marry Katrina, since he was a free man. Irked with the question, Salman got into a fight, dropped the soup, and left. Jhanavi’s mouth was left open.

Media, being quite enraged with Salman, ran the news over and over again. Jhanavi had indeed become famous, as famous as Salman himself in the minds of Indians worldwide. She should have been happy, she had finally achieved what she had wanted. When I visited her the tenth day after her fast began, her mouth was still open, waiting for the soup that never came. Feebly she asked me, “Will the government intervene now, because I am as famous as the Iron Sharmila? Will they force-feed me like they did to her? Can Sambhar be fed directly to the nose? Will it burn?” Weakness had made her mind hazy.

I did not have the heart to tell her that the government did not really care about her cause as it was for a private person. A minister in the ruling party had made a statement that the Mumbai Film industry had to deal with this on their own. It was not their responsibility or prerogative. “Trending News”, meanwhile, had managed to make the most out of the issue. They organized interviews with leading psychiatrists, film personalities, sports stars, and leading ladies about the concept of fandom in India. A journalist award was also announced for them.

Exactly twenty days after Jhanavi’s fast had begun; Salman announced a new film with a new starlet. The entire media were at his doorsteps covering him 24/7.Trending News got bored with her. They moved on to other topics. No newsman was left at her canopy. No one was interested in her anymore. Rashi never got a call from Salman’s office.

We were finally able to convince Jhanavi to end the fast and let go of her ‘cause.’ The family returned home 100 pounds lighter but 100 degrees wiser.

Be First to Comment