Pynchon’s Dystopia

Dys by Thomas Pynchon

Imaginary review by Dan Geddes

A new Thomas Pynchon work is always an event, and his devoted readers will treasure his latest effort, Dys. Dys is clearly dystopian fiction, but it is still a Pynchon work more than anything else—a wickedly funny masterpiece about power, history, and conspiracy. The picture of encroaching fascism in America that Pynchon sketched in his underappreciated Vineland has been painted more luridly in Dys.

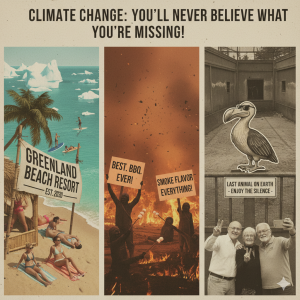

Americans in Dys live in constant fear and shock, in a state of perpetual war, and under the eyes of increasingly penetrating electronic surveillance. The skies are policed by millions of pesky VDs (flying video drones), which spot-check everyone’s behavior on a daily basis. But Americans have taken the surveillance in stride; the home version of VDs (packaged as flying pigs) are hot sellers in the burgeoning personal reconnaissance market. Everyone is spying on each other. Life is like the movie The Truman Show, except that everyone is on TV (or the web).

In Dys, everyone except the super-rich live under VD surveillance, the images from which can be seen instantly over the internet to anyone who tunes into a person’s VD cam site. Everyone watches everyone else (and himself) on TV. If Vineland described the mind-deadening banality of TV, TV in Dys is mostly surveillance footage, war footage, or COPS Around the Clock™.

Like many Pynchon works, the story is a quest, this time of a young woman (Ginger Vitis) looking for her husband (Ellsworth Vitis), a leftist writer. Ellsworth is captured from their Florida home by paramilitary forces in a pre-dawn raid. Ginger works her way through labyrinthine bureaucracies encountering only stony silences about Ellsworth’s capture. The Federal Police finally produce some “evidence” concerning his disappearance, but Ginger identifies these as crude forgeries, especially Ellsworth’s ridiculous “prophecy” that he will be captured by Pakistani militants posing as paramilitary police, or his obviously doctored “suicide note.”

Frustrated by attempts to discover her husband’s whereabouts, Ginger begins researching Constitutional law in order to determine her legal strategy to get Ellsworth back. She soon learns that the Patriot Act has dissolved the Bill of Rights. (“Wow! That wasn’t on TV,” she laments.) She begins to devour works about the 1960s, a time before her birth that she believes represented the American people’s final attempt to resist state power. Watching the video drones hover outside her window, she is comforted by the thought that a free society was once possible.

With her life destroyed, Ginger accepts the offer of her college roommate, Dizzy Trollope, now a graduate student in history, to visit her in Amsterdam. In Amsterdam, Ginger and Dizzy are free to talk, even if their passports have embedded GPS technology to track their whereabouts, and most of the city center is under VD surveillance. In Dizzy’s apartment, they smoke semi-legal Dutch marijuana, while Dizzy, who has been researching “The Plot” for years, tells her friend the “true history of the world.”

Dizzy has seen the archives of a secret society now known only as The Plot. The Plot experienced many name changes, but was started in 18th century France by a group of seminary students devoted to interpreting Nostradamus’ Centuries. The exegetes violently debated the meaning of some quatrains. Extremists vowed to actively fulfill the apocalyptic prophecies. A secret committee created a blueprint for world domination, which they estimated would take about 250 years to execute.

The seminarians’ plan to infiltrate secret societies, international banking and diplomatic circles, the press, The Church, and global intelligence operations.

Dizzy’s long monologue traces The Plot from the French and American Revolutions through the present day. Even “the Holy Sixties themselves,” Dizzy says, were just another state media production of The Plot (however real the revolutionary vibes seemed at the time). The countercultural leaders of the 1960’s were usually CIA operatives. Gloria Steinem? CIA. Bummer.

Ginger is skeptical about most of these theories. She is further confused by listening to other weird theories from Dizzy’s wacky Dutch friends, Jaap and Saskia. Saskia believes The Plot didn’t start with the French at all, but with a mysterious group known only as the GDG based in 17th century Amsterdam.

While conspiracy buffs may drink in these tantalizing suggestions like mother’s milk, others are left uncertain as to Pynchon’s intentions. While we share his concerns about civil liberties, how much of Dizzy’s pot-addled conspiracy does Pynchon (expect us to) take seriously? Is he encouraging us to research history, or is he only trumpeting his theme of history as fiction?

We’re not sure, but at least Pynchon allows his characters and readers a spark of hope. The deeper Ginger and Dizzy probe into the conspiracy, the more they encounter the forces of entropy undermining the totalitarian leviathan. Even among the Elite, the 100 families that Dizzy believes run the world, there remains a refreshingly human tendency for intrigue and internecine warfare.

For a determined truth-seeker such as Ginger, the system actually proves porous enough that she finally discovers Ellsworth, still alive, but now exposed for having sinister connections to German pharmaceutical companies.

Pynchon maintains his high standards for density, allusion, and humor. Pynchon here is as multi-dimensional as ever. He can describe dark settings and actions, and also display his more ludic side. But some readers may find his habits irritating. He relishes spoofing TV shows and inventing ridiculous song lyrics. He gives his characters flat, silly names that weaken their emotive impact.

Despite these criticisms, Pynchon is clearly one of the few living masters. Dys is a dense textual tapestry. Urgency informs this work, as if Pynchon is aware that his efforts to warn us about encroaching state power are far too late. Dys gives us a strong suggestion of how Pynchon views our new Orwellian realities, such as the Patriot Act, the Department of Stateside Security, and the War on Terrorism.

Dan Geddes

Note: This piece first in appeared in The Modern Word in their Imaginary Book Review contest.

See also:

The Crying of Lot 49,

Gravity’s Rainbow,

Vineland,

Bleeding Edge and

Inherent Vice

Be First to Comment