Spoiler alert: This essay contains plot-spoilers.

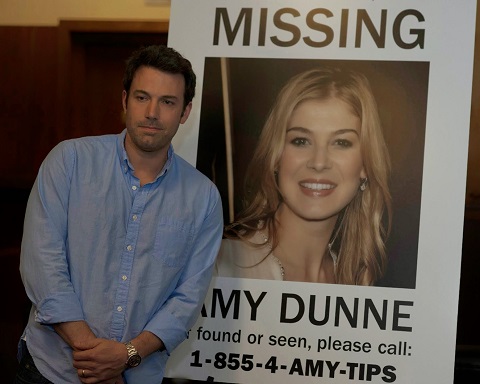

Gone Girl (2014) is a satirical commentary on the state of contemporary marriage. It is a well-made film, following a clearly constructed, if ultimately disturbing, storyline. The characterizations are exaggerated enough to give the movie an abstract, unrealistic quality. The movie’s goal of serving up sharp social commentary is sometimes at the expense of showing realistic individuals. Because the characters are not realistic, it is not expected that we care for them as characters as much as archetypes. The characters serve the plot so dutifully that the movie often feels artificial and scripted. But if the major characters in Gone Girl are clearly weaving stories around their own lives then the visibility of the movie’s plot turns supports the theme. It’s just another noticeable weaving in a story about the stories we tell others, and that the media tells us.

Amy’s life feels predetermined by her fabulist parents (Rand and Marybeth), who write the popular “Amazing Amy” series of children’s books loosely inspired by her life. In their books, however, they improve upon Amy’s life, taking her shortcomings and exaggerating them into Amazing Amy’s perfections. Amy herself (Rosamund Pike) is beautiful and intelligent, and she has her own great expectations for her life and of that of her husband, Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck). Pike convincingly portrays Amy’s relentless competence and willingness to do anything. She will later weave her own stories around her life as her parents did, including devising clue-based treasure hunts for her anniversary present for him.

The first third of the movie focuses on Nick’s perspective. Amy is missing, and he appears concerned, but not concerned enough. He is photographed smiling goofily at the emergency meeting called by the town to find the missing Amy. Soon the clues pile up. Detective Rhonda Boney and Officer Jim Gilpin (Kim Dickens and Patrick Fugit) suspect Nick of murdering Amy.

TV Personality Ellen Abbott (Missi Pyle) also paints him as an uncaring sociopath. Some of the most effective satire is pointed at media sensationalism and the false sense of intimacy it offers us into the lives of the two main characters, who hardly seem to know each other.

This first part of Gone Girl seems almost like a normal thriller or a detective show. Affleck’s character says it’s like he’s on CSI. Your reaction to the first part of the movie depends on much you know about the movie from trailers, reviews, word of mouth. It has surprises in any case.

Despite his prominence in the beginning, Nick is the supporting antagonist in the intra-marital struggle. He is a player, but he is no match for Amy. He makes a valiant attempt to exonerate himself despite his apparent guilt; he hires Tanner Bolt (Tyler Perry), a lawyer who specializes in defending men accused of murdering their wives. Tanner tells Nick that the main battle in high-profile cases is how it plays out in the public eye.

We start to get Amy’s perspective, via voice-overs, after her diary is found by the police. Amy appears as a voice-over “from the grave,” chronicling her husband’s uselessness and eventual abuse, climaxing in her (apparent) murder. When we shift to Amy’s perspective and learn that she is alive and has faked her death, the revenge is supposed to be sweet (if wildly disproportionate to Nick’s failings). We see Amy’s plan to be thorough and masterful. She feels totally justified. She is at her best here, plotting her escape from her failing marriage. Faking one’s death is shown as the ultimate escape for those with the means to pull it off. Here it has almost a Shawshank Redemption quality to it. She has liberated herself and avenged the husband who has wronged her by cheating on her with his sexy college student, Andie (Emily Ratajkowski).

But Amy starts to lose our sympathies. She is incredibly disdainful of people (almost everyone except her parents), such as her “best friend,” Noelle, who she disdains and only befriended to frame her husband. It’s a great touch, because the friendship starts out as a mystery to us. Affleck’s unawareness of her “best friend” indicts him in minds of the police and the public. It’s another sign of a husband so out of touch with his wife’s life that he would be jaded enough to kill her. But the fake friendship telegraphs her elitism. She has framed her husband for murder. He has also been charged with murder and even crucified in the public eye. If convicted, he faces the electric chair in Missouri.

Gone Girl’s satire is not immediately obvious. The movie is a commentary on the horrors of contemporary marriage. Marriage is depicted here as a lonely and even competitive situation. Why couldn’t she just divorce him? Because then there wouldn’t be a movie. If she only would have put as much effort into the marriage as she had into her plot to frame him for murdering her, then you would imagine the marriage would have worked. But she has a psychotic self-regard. She regards her husband’s possible execution for her murder almost as a mercy killing, because their marriage has lapsed so far from her ideal. She finds her marriage so bad, that she is planning to commit suicide over it as well. This somehow engenders sympathies from some viewers. From her perspective it’s fatalistic, like a lovers’ leap situation. If she can’t regain the passion of her early marriage then she’s better off being dead and so is her husband, case closed.

The movie is in the tradition of what used to be called the battle of the sexes. This is marriage as total war. Author Gillian Flynn said she had a moment where she feared: “Oh no. I’ve killed feminism.” She later decided that it wasn’t the case. Taking the “perfect woman” and revealing her to be nearly a master criminal and cold-blooded killer is a risky move for a feminist author. The movie doesn’t kill feminism as much as play on gender stereotypes and highlight some unsavory terms in contemporary marriage. Amy has a consumerist sense of entitlement to marriage and its trappings. His greatest crime seems to be using the same pickup line with other women as he once used to help win his wife. They all weave stories, but he reused a line, thus cheapening her.

When she runs away it’s surprising Amy would end up at a camp site where she would end up socializing with Greta (Lola Kirke) and Jeff (Boyd Holbrook). But it shows more class distinctions and adds another layer of social commentary. The camp scenes have a relief quality to them. When she is robbed there by the trailer trash it feels like a forced plot twist. I like these characters, Greta and Jeff, but I thought Amy probably would have been smart enough to seek more private quarters, or at least hide the wad of cash after they see it (or at least separate the big bills from the small bills she told them was in it).

So she is forced to call on her last reserve, her old boyfriend Desi Collings (Neil Patrick Harris). He is affluent and he adores her. So she can use him? Yes. But why doesn’t she want to stay with him? Why can’t she love him either?

Nick knows that in his dramatic TV interview with Sharon Schieber (Sela Ward) he only has to reach Amy, not the millions in the audience. His confession of infidelity and declaration of love for Amy reach her (and turns the story). She knows it’s not totally sincere. She responds favorably simply because he had the right stuff to make the big gesture to save their marriage. This is an important (and unexpected) plot twist.

In the end, it’s also unbelievable that she could get away with killing Desi. Perhaps it seemed inevitable to writer Gillian Flynn and director David Fincher. Or maybe they needed a sensational event to climax Act 3 of the script. The killing shocks us. Amy is the person the media showers praise on, and, neurotic as she has seen to be, here she is shown as a cold-blooded killer.

Fincher and Flynn suggest that from Amy’s perspective of getting away with the crime of killing Desi, that she had public opinion so blindly in her favor that they were relieved at her return, and so never suspected her of murder. But wait, don’t they know she killed him? The police assume that it was justified because it he had presumably captured her and held her captive for four weeks.

Officer Rhonda, an important supporting character, totally believes Nick now that Amy had faked her murder and actually murdered Desi. She says there’s nothing she can do because the FBI took over the case. But Amy even knew how to play to the surveillance cameras in Desi’s home, as she knows how to play the camera in the world.

It’s unbelievable that Nick could stay with her after what she did to him and his sister, as well as killing Desi. How could he sleep at night? He was smart to lock his door at night. Amy has become a hyperbolic American psycho, a caricature like the Glenn Close character in Fatal Attraction. The fact that he does stay with her because she becomes pregnant (she took sperm that he had earlier donated to the sperm bank) suggests that fathers will go through anything to be with their child. He is an allegorical father. A real man would more likely fight for joint custody and go back to proving to the law that she is a psycho killer. Instead, the moral seems to be that some sacrifices and moral compromises are required in order to save the modern marriage. In this case, the woman “wins” the battle. It doesn’t “kill feminism,” but it makes marriage seem ugly.

Just as Amy’s parents constructed a fake reality of her life in the children’s books, so she constructs fake story after fake story: befriending her neighbor, faking her death, framing her husband, lying to the people at the camp site, tricking her ex-boyfriend Desi, killing him by fooling his own surveillance cameras, and telling more fabricated stories to the police upon her return.

Gone Girl has its own story logic. It’s not realistic that anyone would do what Amy does. Gone Girl often has a fabulist, magic realism to it, determined by the logic of the creators’ views on marriage, feminism, and identity. Despite a completely unrealistic Act III, Gone Girl is a movie well-designed to influence our cultural conversation about marriage and relationships.

Be First to Comment