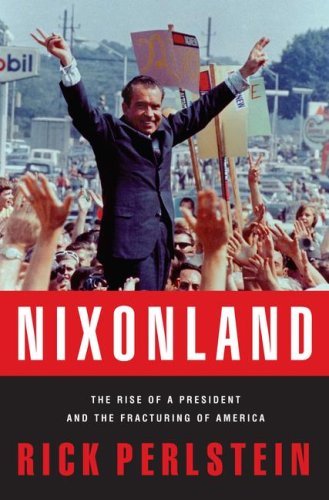

Rick Perlstein

Review by Dan Geddes

Nixonland reads like a tragi-hilarious movie reel of the Sixties. Perlstein’s narrative is sweeping, colorful and dense as it covers the American political and cultural terrain from LBJ’s liberal landslide in 1964, through Nixon’s comeback in ’68, and landslide re-election in ’72.

Nixonland tries to answer the question of how things changed so much in such a short period. The book certainly serves to show, perhaps as well as a book can do, what the political/cultural environment of its period was like. Perlstein’s implicit thesis is that white backlash against the Kennedy/Johnson Great Society initiatives brought America the return of Nixon. The South, as well as white, blue-collar labor nation-wide, were key Democratic blocs that began to desert them for the Republicans during this period. Southern leaders, led by Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, were resisting integration of schools and housing. After the topsy-turvy years of the urban riots, civil rights marches, and college anti-war protests, many northern whites had also thought things had gone too far. The “law and order” issue may have been introduced by Ronald Reagan, during his successful run for California governor in 1966, but Nixon was able to use it to his advantage in the ’68 Presidential race. Perlstein’s vivid description of the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago—with chaos on the floor, and a battle between police and protesters in the streets outside—conveys what the average TV viewer at home might have thought of such a proceeding. The Democrats were a fractured party, rent by anti-war tribune in Eugene McCarthy, versus the party functionary Hubert Humphrey, who vaguely supported continuing the Vietnam war in the way of LBJ.

In an epic with many strong characters (Lyndon Johnson, Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Strom Thurmond, many others), Richard Nixon takes center stage, as the master political hack. Nixon’s lifelong striving (Perlstein works in just the right amount of back material about Nixon) reached its final goal with his historical political comeback in 1968 after his crushing defeats of 1960 and 1962.

The fact that Nixon himself was not born into the Eastern Establishment, and worked so hard to climb his way up to the top, appealed to many voters. He portrayed himself as a hard-working guy like them. Nixon played this card throughout his career, notably in the 1952 Checkers speech, where he admitted on national television that he still owed his parents money.

Perlstein calls strivers “Orthogonians” after a club Nixon started at Whittier College (in contrast to the “Franklins,” who are the beautiful people, the popular crowd). Nixon realized early on that there were more strivers than well-born in this world, and he courted their votes avidly his entire career. This tactic was later used by Republican Presidents like Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush, who presented himself as a simple, down-home guy, even though he is the son of an Eastern Establishment President.

Nixonland is a must-read for those seeking to understand the ongoing “Red-Blue” divide in America. Nixon’s achievement in recapturing the White House for the Republicans sprang from his insight into white backlash. Nixon didn’t create the modern liberal/conservative fractiousness, but he deliberately exacerbated it for his political purposes. Nixon’s 1968 and 1972 presidential campaigns laid down the tropes that were to reappear in so many subsequent elections: liberals as back-stabbing traitors; liberals as war saboteurs; liberals as condescending to the working classes; liberals as propagandizers of a decadent morality.

While there is nothing new under the sun, the elections of 1980-2008 bear an uncanny resemblance to the elections of 1968 and 1972 (the Republican southern strategy, scaremongering about welfare queens, vague proposals for ending an unpopular war etc.) LBJ’s Vietnam War was an even greater tragedy for discrediting an administration that tried to bring a better social safety net to Americans. In part, because of its failure in the 1960s, many Americans are still distrustful of a European-style public sector, even if it would seem to be in the best interest of the strivers.

Perlstein doesn’t prove his thesis that Nixon’s rhetoric still shapes contemporary political dialogues. In order to do that, his work would have to shuffle between his 1965-1972 period and later events. In fact, Nixonland says very little about this later period. Instead, Perlstein works implicitly, laying out the politics of his period in spellbinding detail, and tempting his readers to hear the familiar echoes. Nixon’s team wrote much of the Republican playbook for subsequent elections and laid the groundwork for the Republican control over the Oval Office for 28 out of 40 years during the 1968-2008 period.

Perlstein leverages new online archives to include dense samplings of newspaper and magazine headlines. Sometimes he gives us several items from the same issue to illustrate the editorial judgments about the relative weight of news events (such as the Watergate break-in relegated to the back pages during the ’72 election).

Reading Nixonland often resembles reading the news of the period on the internet (or on microfilm). Perlstein selects the most telling articles and quotes from them liberally, to add an extraordinary level of detail to his narrative.

Perlstein condemns the excesses of the police crackdowns on political dissent. However, his chronicle will leave little doubt in many readers’ minds that the anti-war movement went past an appropriate line of civil disobedience in some cases. This also discredited those in the movement who were continuing non-violent dissent. (Many charge that the more violent members of the anti-war movement were government infiltrators in the COINTELPRO program.)

In any event, the political violence of the Nixonland period is almost not to be found in American society since that time. Leftists might argue that the police and surveillance apparatus is so advanced that organization of groups such as the Black Panthers is no longer possible. Many others view this is as a positive development.

While Nixon emerges as the appropriate leader for the crackdown, his dirty tricks finally caught up with him. In the ’72 campaign, we see Nixon sabotaging the candidacies of Democratic challengers. Eventually, the Watergate story begins to break, but not quite in time for the election. As a reading experience, wishing for a denouement, it’s a bit unsatisfying to finish 750 pages, and be left hanging with Nixon’s career just under attack about Watergate. Perhaps Perlstein is saving it for a sequel.

In any case, Nixonland features many hilarious moments, whether the target is Nixon (his social awkwardness, his mendacity); the shallow opportunism of politicians of either party, or even idealistic excesses of the New Left. When the story is tragic, such as during the riots or the Vietnam war, it remains equally exciting.

Nixonland sets a high bar for popular history.

Be First to Comment