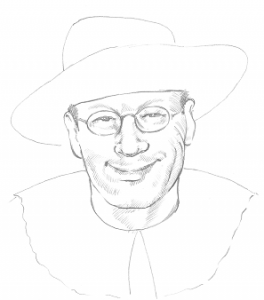

Imaginary review by Dan Geddes

The great German composer and musicologist Felix Spielenhammer left an indelible mark on musical history. His development as a composer and theorist mirrors developments in twentieth century music as a whole. His death on 14 May 1995 was mourned by true music lovers everywhere.

Although he began composing at the age of five, Spielenhammer’s creative output was small considering his nearly 100 years of life. Aside from his masterpiece, the incomparable “Cacophonous Symphony” (Opus No. 4 in F Minor), he produced only two piano concertos, one violin concerto, one movie soundtrack, one completely disastrous opera, two musical comedies (one never produced), a TV theme song, and a mound of unfinished scraps of music, some of which he later admitted should never have been performed publicly. But aside from his musical output, Spielenhammer published several volumes on the theory of music that influenced many 20th Century composers.

Spielenhammer: Early Life

In a long life replete with the most absurd ironies, it comes as no surprise that Spielenhammer, like many artists, grew up in the midst of an unusual family life. Felix, born on April 1, 1897 in Essen, Germany, was the only son of “Mad” Rudolf Spielenhammer and his Bridgette. A daughter, Cosima, was born in 1900. The Spielenhammers lived in terrible poverty throughout young Felix’s childhood, supported only by Bridgette’s job in a munitions factory. “Mad” Rudolf had been stone-deaf since the age of ten, but tried reluctantly to earn a living through a series of odd jobs: coachmen, bartender, butler, numbers runner, and piano-tuner.

Forced to rely mainly on Bridgette’s factory job, the Spielenhammer’s lived in a noisy one-room flat next to the railroad tracks in the little town of Essen. The family was outcast, chiefly because of Mad Rudolf’s scandalous reputation, earned during violent drinking bouts that often landed him in the local jail. Mad Rudolf was known to visit prostitutes, assault the town constable, disrupt masses with loud and outrageous claims about Pope Leo XIII’s excessive appetite for cold cuts, and shriek like an animal in the town square at all hours. He had married Bridgette, the cherished daughter of a wealthy merchant family, on the strength of 100,000 Marks he had won at the roulette wheel in Baden-Baden, the family forcing the unwilling daughter on young Rudolf, because—though beautiful—she was still unwed at the then spinsterly age of 23.

But with the gambling winnings quickly spent on Rudolf’s vices, and with two young children to support, Bridgette was forced to take a job as a drill-press operator at the local Krupp Munitions plant—an unusual occupation for a married woman in Wilhelmine Germany. Fearful of leaving her young children with Mad Rudolf, Bridgette brought her young children with her to the munitions plant, where they were treated to the harsh sounds of riveting and pounding machines for ten hours a day, six days a week. Musicologists believe that this experience was to have a lasting impression on young Felix, whose works were later to feature clanging disharmonies, deafening discordance, and an excessive use of violent cymbal smashing, among other obnoxiously loud sounds.

But the infant Felix was also exposed to more melodious sounds. Bridgette herself was a competent pianist, and spent her Sunday afternoons teaching the young boy how to play on the family piano. Although he was prone to pounding the instrument harshly, seemingly in imitation of the sounds he heard during the week, young Felix soon mastered a few basic keys, and by the age of four could play fairly reputable renditions of popular German folk melodies.

In the midst of this terrible squalor, young Felix became the only hope of their desperate lives. At age six he composed his first popular medley, entitled Armlicher Mann, Sehr Sehr Armlicher Mann (“Poor Man, Really Really Poor Man”), which, when copyrighted and published, brought the desperate family a helpful thousand Marks a year. But Mad Rudolf squandered much of this sum at the roulette wheel.

Young Felix soon began attending the local school where his peers subjected him to violent taunting about his ugliness. He had inherited his father’s snub nose and beady eyes, and even at the age of five seemed to possess a receding hairline. His atrocious wardrobe didn’t help matters, as it seems that the boy. Felix was soon in the throes of despair, and even refused to play the instrument he already had come to love. Bridgette was powerless to get the boy to return to the piano, her efforts only earning her various projectile food offerings, as young Felix hurled plates of potatoes or noodles at her in disgust. Bridgette’s attempts to teach young Cosima the piano were totally fruitless, as the young girl, though possessed of perfect hearing, pretended to mimic her father’s deafness out of some misguided sense of pro-fatherly love.

Despite a gnawing sense of social inferiority, Felix eventually returned to the piano, spending countless hours on the instrument and achieving a technical competency—albeit far from virtuosity—that far outstripped his mother’s. Bridgette was growing haggard from her years at the munitions plant. Felix was viewed as somewhat idiotic and eccentric by his teachers, who doubted he would ever amount to much. One schoolmarm even wrote he would make “excellent canon-fodder” should war break out between Germany and France. But his mother kept him out of remedial classes. Cosima proved unmanageable early on, trying to incite even her kindergarten class to sing “Deütschland Über Alles.”

By the eve of the First World War Spielenhammer’s abilities had attracted notice from the neighboring nobility. Count Max Rheingold became his patron. Felix accompanied Count Rheingold to St. Petersburg in the spring of 1913, and music legend has it that young Spielenhammer was the first of many spectators to throw fruit at the musicians during the first public performance of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rites of Spring—declared a masterpiece only twenty years later. But Felix fell in love with the musical culture of St. Petersburg, and, at the age of 16, was sentenced to a night in prison for running wildly down the streets of the capital yelling: “Tchaikovsky is God!”

When war broke out in the summer of 1914, Spielenhammer, although only 17, managed to enlist in the Prussian army, and saw action as an artillery man on the Western front. His front line division was subject to nearly constant bombardment by a powerful battery of British artillery, and casualties ran high. Spielenhammer himself, however, was to emerge from the war without a scratch, his fellow soldiers reporting that he would scribble feverishly on music paper throughout the bombardments, as if at the peak of inspiration.

Spielenhammer returned to Essen after the Armistice of 1918 to find his family in worse circumstances than ever. Mad Felix’s mocking efforts to master the violin had only earned him fierce beatings from enraged neighbors, and his profligate spending had grown uncontrollable. By now Rudolf was banned from all music stores within a 50 kilometer radius, and most other shops as well. The family’s debts were by now astronomical and could never be repaid, and the piano and most of the furniture had long been carried off by embittered creditors. Bridgette had grown weaker from long hours at the Krupp plant, and from her desperate attempts to keep the family together. Cosima had dropped out of school, and was destined to marry the village idiot, an unkempt, mysterious creature known only as “Otis.”

Mad Rudolf wept uncontrollably on seeing his son return from the war, but after Bridgette explained that his father had been counting on receiving Felix’s military pension after the boy’s expected death in battle, Spielenhammer became completely disillusioned with his family. He received a stipend from the aging Count Rheingold in order to study music in Vienna, and after promising to send his mother some money, he was soon on a train for the music capital of the world.

Early Career

Armed with Count Rheingold’s stipend, young Spielenhammer soon began to slip into the debauchery of his father, spending much of his funds on the high-class prostitutes that lined Vienna’s Ringstrasse. His auditions at the finer conservatories proved disastrous. The young pianist was obviously very nervous, and one judge simply wrote “Ach, die Pein! die Pein!” (“Oh, the agony!”) on Spielenhammer’s evaluation form. Meanwhile, Spielenhammer supported himself as a piano tutor.

His first break came when he decided to attend a public lecture given by the innovator of atonal composition, the great Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg’s revolutionary “atonal” theory of music held that the traditional eight-tone octave structure should be scrapped in favor of a revolutionary, if less melodic, twelve-tone structure. Schoenberg and the atonalists that followed were to enjoy great appreciation among music elitists during the course of the twentieth century.

But Spielenhammer, a fiery twenty-one year old by 1918, was soon viewed as a radical even by Schoenberg and his disciples. Spielenhammer, after ingratiating himself into Schoenberg’s circle, quickly argued that music should not be grounded on any kind of traditional scale whatsoever, but should aim to reflect the sounds that the modern working man was likely to hear in his daily life. To illustrate his point Spielenhammer quickly composed his now infamous Opus No. 4 in No Major, which, through its use of clanging disharmonies, earsplitting discords—as well as railroad, industrial and even animal sounds—was to set the world of music on its head.

Before the first public performance of Opus No. 4, Spielenhammer published a musical treatise entitled Der Klang des Klanges (The Sound of Sound) which attempted to prepare musical audiences for the thunderbolt he was about to unleash on the world of music. First published in the Vienna Schlechtzeitung, Spielenhammer’s seminal article argued that:

Modern music should represent the anarchy of modern life; it must be structureless, spontaneous, unpredictable. No longer is man in nature. He no longer hears singing birds. Operatic arias and chamber music are purely for sissies. What we deem to be beautiful in music, is, as in all art, simply a product of our breeding. If heard often enough, even fingernails scratching a chalkboard—again and again and again—will begin to sound pleasant to us, even comforting in a way…The old music is now gone forever.

Although Schoenberg and the more respected composers of Vienna soon denounced Spielenhammer as “an obvious fraud,” news of a revolutionary breakthrough in music had brought the anticipation for the opening of Opus No. 4 in No Major to a fever pitch.

Performing the Opus placed completely unprecedented demands on the orchestra, as the more traditional string and wind instruments were joined by a vast and motley assortment of other objects capable of sound. To stage his production, Spielenhammer was forced to write a desperate letter to Count Rheingold—now, by all accounts, completely senile—for financial backing. But with the necessary funds soon in hand, Spielenhammer was able to procure all the things he needed to stage his masterpiece. He was to stage it outdoors at noontime, on October 6, 1919, near the large fountain of the Ringstrasse in Vienna’s center. Admittance was to be free to the public.

Besides the traditional orchestra, the program for the premiere of the Opus listed: “10 large gongs, 4 kettle drums with industrial-strength skins, one sex-starved cow, several recently soiled babies, 3 old Mercedes with inoperable starters, one Howitzer cannon, several rounds of explosives, a cat, a bathtub, a harmonica, a hairy man needing a bandage removed, 5 divorcees with vindictive streaks, an incompetent bugle player, and an unwashed duck,” among many other “instruments.”

October 6th proved to be a sunny day, ideal for a noontime concert. Vendors sold beer and sausages from sidewalk stands.

From the first violent thwangs on the gongs by some unruly delinquents—hand-picked by Spielenhammer himself—audiences knew they were in for something special. The violin section began playing something sounding suspiciously like The 1812 Overture while the wind section simultaneously played the opening theme from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Spielenhammer, perched on a high, specially constructed platform, made wild gestures with his unusually large baton, gesturing for everyone to play louder, and when unsatisfied, approached the musicians and began randomly exchanging their music with others while the performance continued, inducing sheer chaos in the string section. Simultaneously he made violent gestures to his numerous “sound crew,” who attempted to start the Mercedes, speak rationally to the vindictive divorcees, change the babies, wash the cat, help the man remove his bandage, fire the cannon, ignite the dynamite, and do unspeakable things with the harmonica and the duck.

The entire performance lasted a scant nine minutes, most of the professional musicians leaving about halfway through, leaving the “sound crew” to continue the performance unsupported by the orchestra. Only now was it understood why Spielenhammer had strictly forbade any rehearsals. As the musicians fled en masse, Spielenhammer was heard to shout “Fine! It’s better without you!” and shake his fist angrily at them, before resuming his conducting with even more maniacal energy.

The large noontime audience was at first curious, then perplexed, and eventually enraged by the thought they had been swindled. Some of the Viennese began to charge Spielenhammer’s platform, and only his loyal delinquents were able to whisk the conductor away by miraculously starting up one of the old Mercedes and driving him through the angry mob at top speed.

Spielenhammer had quickly become the first persona non grata in the newly formed state of Austria. Franz Schuler, the conductor of Vienna’s prestigious Staatsoper (State Opera), publicly petitioned the mayor to have him banned from Vienna for life.

Fleeing to the newly formed Weimar Republic of Germany, Spielenhammer justified himself and his music in a long newspaper article entitled “On the Idiocy of the Viennese.” Here he pilloried Vienna as being “a city beyond decadence,” and lambasted their “resistance to innovation” in music.

But Spielenhammer found himself much more at home in Weimar Germany—perhaps the most decadent flowering of German culture of all time. Although his music publisher was willing to publish the score of Opus No. 4, critics were perplexed by the complete lack of musical notation, one critic warning readers that:

…in it we find nothing that can meaningfully be called music. Instead we only find a long list of ‘instruments,’ and a series of instructions: ‘bang drum fiercely,’ ‘beat cow,’ ‘fire cannon,’ ‘play Beethoven atrociously’. All in all it doesn’t add up to much. It is obviously intended to be something ‘beyond music,’ a critique of all that is ‘too orderly and rigid’ in traditional harmonic structures. After a bad day at the office, even Schoenberg is tolerable, even cathartic; but this is simply going too far.

Although embittered by the poor public reception of his new “meta-music,” Spielenhammer, vowing to make a living as a composer at all costs, quickly returned to more traditional forms, and began writing for the then growing musical theater circuit in Berlin. His first musical comedy, a merry romp entitled Hansel and Gretel Underground, was a continuation of the popular German fairy tale. The young children, after following a misleading trail of breadcrumbs, are trapped by a sinister wolf/entrepreneur named “Yeastless Ludwig,” and forced to work long hours in his Wunderbrot bread factory.

Despite its serious themes and scathing social commentary, Hansel featured such memorable popular songs as the rollicking “We Eat Too Much,” and the naughty “Why, Tell Me Why, Is Incest So Wrong?” Even Yeastless Ludwig is given to song, and his touching solos “Gretel, my Gretel,” and the gut-wrenching “Who Put the ‘Bad’ in the ‘Big Bad Wolf’?” offer tragic interludes in an otherwise farcical musical comedy. Although touching on such forbidden themes as bestiality and incest, the bulk of Hansel and Gretel Underground is comprised of spritely, comedic numbers, as Spielenhammer successfully kept the play from degenerating into the “ponderous critique of industrialism,” that one critic saw in the work.

Flushed with the minor success of Hansel, Spielenhammer felt professionally secure enough to marry his first wife, Lotte Karlsbad, a former prostitute turned singer-actress, whose first professional acting job was the role of Yeastless Ludwig’s pet iguana in Hansel. Some doubted the wisdom of the marriage, Felix’s friend Franz Kruger describing Lotte as “a slut,” and predicting marital disaster as well should Spielenhammer’s career suffer the slightest downturn.

Although Hansel had seemingly given him years of financial security, the winter of 1922-23 saw the worst outbreak of hyper-inflation in German history, and the savings of most middle class families were completely wiped out. A loaf of bred cost a wheelbarrow full of Marks. Workers had to be given large pay raises of increasingly worthless Marks—almost daily—to keep up with spiraling costs.

But as a composer, Spielenhammer had no steady wages to rely on; Hansel was soon canceled, and many theaters shut down completely. The newlyweds were soon desperate, and Lotte threatened to resume her former profession if Felix did not take swift action.

His response to this threat was the creation of the never-produced musical comedy Fame and Famine, which featured such distasteful songs as “Brother, Can You Spare 1.8 Million DeutscheMarks?” and the scandalous “Maggie the Spoon”—which to his dying day Spielenhammer fiercely avowed had been stolen by the young Kurt Weill, and later transformed into the wildly successful “Mack The Knife.”

Middle Years

With his royalties from Really, Really Poor Man and Hansel now being paid to him in almost worthless German currency, Spielenhammer fled to the United States in the spring of 1924, accompanied by Lotte. His former “association” with the great Schoenberg gave him access to the elite music circles of the United States, which discounted Schoenberg’s daily, denunciatory trans-Atlantic telegrams about Spielenhammer as mere “artistic quarreling.” He was embraced as yet another German musical genius.

But exactly at this time we see the beginnings of a strange lull in Spielenhammer’s musical output. Although he was offered handsome sums to produce a musical comedy, or indeed any complete musical piece for New York audiences, he simply could not write music any more—“not one note” as he was to complain in his journals. Perhaps he could not adapt to American culture; perhaps he was jarred when Lotte inexplicably slapped him in the face one night and dived to her death underneath a moving subway car in Grand Central Station—musicologists still debate the issue. But what is known is that a grief-struck Spielenhammer, whose musical output was scant during his eight years in America, took a professorship in music at the City College of New York, where he began work on a definitive, multi-volume theory of music, entitled A Theory Of Music, which is now considered a milestone in musicology.

Spielenhammer argued that a piece of music should be first understood and listened to as a story. “It has long been understood that rhythm and pitch of music determined its mood: happy, playful, ponderous, angry, triumphant; but rarely has it been understood that music can and should be used to convey the entire story of a man’s life.” The progressing rhythms of a piece, often largo then andante then allegro then vivace then moderato, signify “the stages of human existence,” how “quick” (“lebendig”) is the “beating of our souls.”

All of this seems too rational to have come from the pen of Spielenhammer, and it is no surprise that A Theory of Music contains more surprising statements: “the greater the grief it induces in us, the greater the piece of music”; “music should make us hate the composer—for his genius”; “I hate most composers and musicians. I really do”; “great music should cause great sorrow.”

Although it was little read and poorly received on its publication in 1927, A Theory of Music influenced later generations of revolutionary composers. Although these composers often bemoaned the rambling, 400 pages Spielenhammer devoted to his personal problems, his more germane discussions of music were “a breath of fresh air” for the young Shostakovich, among many others.

Despite ominous warnings from his German correspondents and friends, Spielenhammer decided to return to Germany in January, 1933—just in time for the Nazi Dictatorship. He arrived in Essen on January 30, 1933, the very day that the Reichstag was burned down in Berlin, precipitating the end of democratic rule. Many German musicians and artists were fleeing Germany just as Spielenhammer returned.

He discovered his parents, however, in better circumstances than before, and even some of the old debts had been repaid. Both Felix and Cosima had been sending them checks, Cosima now earning a solid living as a ghost writer for the Ministry Of Propaganda. Otis, predictably, was unemployed.

Faced with the prospect of seeing Mad Rudolph all day, Bridgette had been reluctant to quit her job at Krupp, but the Gestapo’s tactics of discouraging women in the workforce eventually persuaded her. Rudolph, although physically healthy, had taken to lying in bed until mid-afternoon, having Bridgette serve him coffee and read him the newspaper.

Meanwhile, Spielenhammer himself was quickly being courted by the Ministry of Propaganda to produce some pro-Nazi music for public consumption. Spielenhammer, who lived in America during the years of Hitler’s rise to power and so was ignorant of his racist program, was at first impressed by the Nazis: that they had restored the shattered pride of the Fatherland and had created plenty of jobs; but later, as their violent anti-Semitism and general oppression became more obvious, Spielenhammer refused to write the propagandistic music they demanded.

But his abysmal patriotic works of 1933-34, his first music in eight years, can be written off as the feeble creations of a temporarily unbalanced individual. Although only mildly sympathetic to the new Nazi grandeur, these works, such as Der Vaterland Ist Brav, are never performed today.

Spielenhammer’s disillusionment with the Nazis soon prompted his 1937 escape to Britain, where he was to spend the Second World War. Cosima, still at Propaganda, declared her brother officially insane, but still appropriated some of his German copyrighted music for parades and marches. She soon released various arrangements of the music, enclosing preposterous Nazi-inspired interpretations, which saw, for example, Yeastless Ludwig of Hansel, as a symbol of the barrenness and decadence of wolf-like Western style capitalism and imperialism; Hansel and Gretel themselves were apparently symbols of the comparatively innocent and oppressed countries of Germany and Italy.

Spielenhammer was outraged at this use of works, but from 1939 on, with war raging in Europe, he was powerless to intervene. Although now seen as somewhat suspect in the West, Spielenhammer was to produce some of his best music during the war. His Piano Concerto No. 1 displayed his characteristic originality in orchestration, featuring an average of one symbol smash per measure, and unexpected stretches of complete silence that musicologists believe reveal a more contemplative and meditative Spielenhammer; others say he simply short of ideas, and had to fill time. Regardless, Spielenhammer’s use of silence was to influence many twentieth composers, most notably the American John Cage, whose Four Minutes and Thirty-Three Seconds featured total silence for its duration, baffling many an audience, but providing musicologists and aestheticians with infinite fodder for speculation.

The war years were to be the most prolific years of Spielenhammer’s career. He attempted to illustrate the principles he had set out in A Theory Of Music, producing a slew of “bio songs” about, most notably, Beethoven, Napoleon, Byron, Goethe, and Bertrand Russell

After the war, in 1947, Spielenhammer staged his only opera, Day Becomes Night, which dealt with his childhood with astonishing frankness. The opera’s characters—“Mad” Rolf, Gretchen, Felix, Cosima and Otis, were obviously thinly veiled characterizations of Spielenhammer’s family. By now the real Cosima and Otis had fled to Argentina, where one day they would make a fortune by staging Spielenhammer’s long-forgotten Fame and Famine, which appealed to Argentine audiences during their years of hyper-inflation in the 1960s and 70s. But Day Becomes Night centered on the character of “Mad” Rolf, especially his drinking and carousing. Rolf, however, is seen as a victim, and is given to eloquent soliloquies on life’s meaning, which for him becomes the systematic avoidance of all work and effort. Predictably, Cosima emerges as the villain, as seen in her efforts to steal Gretchen’s wages for Otis’ outlandish inventions—such as a car that runs on brainwaves.

But Spielenhammer himself was not to maintain his creative output. By the early 1950s we find him copyrighting single stanzas of music—hundreds of them—which he was simply incapable of merging into any creative whole. He was appointed Professor of Music at Weimar, but was only able to perform his duties for a few years. But he began teaching from his Theory of Music, and eventually was to convince other professors to make his book a standard work.

By 1960, Spielenhammer was retired, and became a recluse, rarely emerging from his villa near Hanover. Visitors would find the aging genius in an appalling state, his villa a disturbing scene of filth and clutter. Three years of mail was strewn about, mostly unopened. Apparently the composer was subsisting only on bread and goat’s milk, and not enough of either, for he was emaciated and apparently dying.

But in the increasingly radical 1960s, musicians were taking a closer look at Spielenhammer’s life’s work, and began to hail him as a suppressed, revolutionary musical genius. His works sold by the thousands and became standard fare for university courses. Theaters in Hamburg, West Berlin, Weimar, Bonn, and Heidelberg performed Hansel and Gretel Underground, and even the forgotten Opus No. 4 in No Major was being hailed on both sides of the iron curtain as masterpiece of modern realism. Spielenhammer was soon a truly wealthy man for the first time, and after fortifying himself with an eccentric diet and exercise regimen, emerged for his first public appearance in over ten years.

He settled in West Berlin, where he quickly became a public nuisance for the authorities, staging absurd anti-nuclear protests: short-lived (afternoon) hunger strikes, poorly attended protests and brief marches—all featuring shocking accusations about the covert activities of the U.S. government. He failed in his many efforts to get himself arrested.

Final Years

Spielenhammer’s appetite for political activism did not outlast the 1960s. A new “revisionary” movement in musicology deemed Spielenhammer “an unadulterated fraud,” and even his well-established tome, A Theory of Music, was out of print by 1972.

Spielenhammer, now in his seventies, vowed to never perform publicly again, nor to publish any new pieces—a somewhat idle threat considering he hadn’t published a stanza since 1961. But with his solidified wealth Spielenhammer, in his last public statement, vowed he would now “enjoy life.” A year later we find him married, this time to Danya Alexandrovna, a ravishing young music student, ostensibly smitten by Spielenhammer’s former genius.

Documentation on the last ten years of Spielenhammer’s life is unavailable. Scholars have been forced to rely on the word of Danya, who has described him as “a soft vegetable, in need of almost constant care and attention.” Despite the demands of caring for her husband, Danya has remained very much in the pubic eye, often appearing in the celebrity pages of Der Spiegel, dressed to the nines, and eating in Hamburg’s finest restaurants with handsome young men—“admirers of my husband” in Danya’s own words.

Spielenhammer’s Legacy

Assessing Spielenhammer’s place in musical history remains a problematic task. Although he enjoyed periods of near world fame, from another perspective his was a transient inspiration, a small flame in the dark torpor of musical stagnation. He lacks the synthetic brilliance of the world’s greatest composers. He was more of a bad boy of music, someone willing to test the boundaries of what “music” really is, perhaps just to show us how much we enjoy the real thing.

Be First to Comment