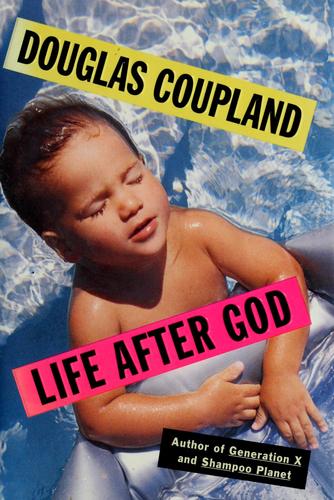

LIFE AFTER GOD.

By Douglas Coupland.

Review By Dan Geddes

From Douglas Coupland, author of Generation X, comes Life After God, a slick and very readable collection of stories, whose only common thread is the same generational angst of the earlier novel.

About this angst Coupland is expert, showing us a world of unstable relationships, potential nuclear holocaust, and worst of all, an all-pervasive consumerist ethic.

Nearly all of Coupland’s characters belong to the X generation, the twentysomethings (some in their early thirties now), displaying the same world-weariness, sophisticated irony, and immersion in brand name products found in Generation X.

The stories in Life After God rarely attempt anything resembling conflict development and resolution, but are more a series of observations, descriptions, and slice-of-life sketches.

In the first story, “Little Creatures,” the narrator drives his young daughter to her grandfather’s. He is separated from his wife, and tries to amuse his daughter with animal stories, but is too distracted to complete them. He ponders “What is human behavior?” and is baffled because only “smoking, body-building, and writing” seem to differentiate humans from the animal kingdom.

“My Hotel Year” describes the desperate lives of a head-banging couple and a male prostitute, who are all too alienated to connect with people. “The Wrong Sun” offers us victims’ descriptions of their own deaths in a nuclear attack. “The Desert” is an account of a man lost in the desert and his inability to communicate with the homeless stranger he encounters.

The final and longest story, “1,000 Years (Life After God),” begins with the narrator’s memory of skinny-dipping with friends as a teenager, and goes on to show their unhappy fates fifteen years later: one is an alcoholic, another a drug-addict, another a drug-addict turned Christian, another is HIV-positive. The march of time has left scars, and the narrator himself is taking prescription drugs for some unnamed malady. He is also withholding a secret from the reader, which he only reveals in the last pages.

The secret?

“My secret is that I need God–that I am sick and can no longer make it alone.” This is indeed a surprising admission from the author who offered us the creedless irony of Generation X, but it carries little impact. The book ends before we see the effects of his conversion. How will his need for God change his life? What sort of God does he conceive? Or is his conception of God what he had scoffingly defined in Generation X as a mere “Me-ism”: (“A search by an individual, in the absence of training in traditional religious tenets, to formulate a personally tailored religion by himself. Most frequently a mishmash of reincarnation, personal dialogue with a nebulously defined god figure, naturalism, and karmic eye-for-eye attitudes”).

It’s a shame these questions are not addressed, because herein lies great potential for the conflict that eludes Coupland as a writer: how does a sophisticated unbeliever–raised in what one story’s epigraph calls “the first generation raised without religion”–develop sincere religious belief without sabotaging himself with his own boundless irony? Coupland does allude to the problem–“…we gained an irony that scorched everything it touched. And I wonder if this irony is the price we paid for the loss of God.”–but we hear nothing more about it. Perhaps Coupland, obviously an autobiographical writer, will discover that this internal conflict could provide him with material rich enough to sustain an entire novel.

In the absence of thematic conflict or character development, what carries Life After God, and makes it easily readable in one sitting, is Coupland’s style. His ironies are humorous at times, and he has great insight into interpersonal interaction, milking laughs from social situations like a good novelist-of-manners (“…his main technique was to pump out negative signals so that women with low self-esteem would be glued to him”).

At the same time, however, his style reveals that his focus is often directed toward surface appearances. As in other books of the same stamp (Bright Lights, Big City; American Psycho) the characters in Life After God are usually described in terms of their appearance at the expense of their upbringing, background, or psychological make-up: their character. Instead we are given innumerable brand names–of clothes, cars, food, furniture–as indices of characters’ socio-economic stations and attitudes. Brand names are also a favorite source of Coupland’s metaphors: “…the decorative kites had ignited like Kleenex”; “the steps I heard were…faintly crunchy like the sound of Cocoa Pebbles being chewed across a table”).

Admittedly, there is less of this superficial focus in Life After God than in Generation X, which was after all primarily an ironic salvo against Society’s artificiality. But even though Life After God‘s jacket flap tells us that Coupland has “unplugged from his previous style,” what has emerged in its stead are fanciful musings about the human condition–charming what-ifs, and imaginative flights that are immediately forgotten (“I myself often have dreams in which I am flying….Needless to say, it is my favorite dream”).

Life After God is also so readable because of its packaging. It is literally a small book (a paperback size hardcover), the text of which is chopped up by Coupland’s cute illustrations on about every other page. Sometimes a three line thought is all that appears on a page, so that of its 361 pages, nearly half of the work is either illustrations or blankness. (Generation X also featured distinctive packaging, being an oversize paperback with humorous definitions of X generation lingo dotting the margins.) Coupland’s illustrations and winsome imagination give it the light feel of a Shel Silverstein book for the angst-ridden.

Coupland himself has now become something of a cult figure for his generation, occasionally offering up poetic fragments on MTV. The success of Generation X has ensured him the freedom to experiment, and granted him the authority to address his audience directly, without aesthetic distance. As long as he strikes the same ironic chords, his audience will be satisfied by wistful insights and brief sketches at the expense of traditional narratives.

Coupland is much like J. D. Salinger after The Catcher in the Rye. He has bewitched the young with a zeitgeist-defining work, discovered God after his literary stardom, and cannot fully disengage the jagged irony on which he built his reputation–however much he might like to preach a new gospel. What Coupland does with his artistic freedom, whether he can use his gifts to create a work that leaves the more lasting impression of literature, remains to be seen.

See also: Book reviews and criticism

Be First to Comment