by Casey Alexander

In between Aztec push-ups, Jim heard the delightful sound of cardboard falling onto his doorstep. He waited in the gym for ten minutes, allowing extra time in case the courier tripped or stopped to admire his tulips. Opening the front door, he seized the box and took it into the house. It could be the belt that he ordered, an accessory for the coffee machine, or his copy of The Artful Homesteader. With a flash of his monogrammed paper and box knife, he split the seal and extracted the contents: a handsome mahogany belt in a sea of Styrofoam peanuts. It was a bit too uptown for the office, Jim thought, but would be ideal for the trip. He set it aside and returned to the gym to struggle through a few more sets. He had fewer heart attacks in the course of a morning when he completed his workout.

His physical systems reset, he switched on the waterproof television that he’d installed in the shower. The presenter had to compete with the sound of cascading water; Jim set the volume on full. He’d tuned in halfway through a public service announcement; it seemed that certain condiments could explode if kept in excess of their shelf life. Jim rinsed the shampoo from his hair, relieved that he was allergic to mustard. He reached for his Imperial Accents towel (the same type, according to the commercial, that was used to dry Charlemagne) and dressed in the crisp cottons that identified him as an agent of commerce.

He made his way downstairs to the café, which he’d decorated in the Parisian style. He’d written the available beverages on a chalkboard above the bar: café con leche, Earl Grey, Ovaltine and so forth. It felt like a white tea morning. Jim poured boiling water into the gold and black iron teapot he’d given himself for Christmas and turned on the local news. There was a special report on cancer of the eyelash. As instructed, he would NOT ignore the warning signs: excessive, uncalled-for blinking; a change in his eyelash distribution; general malaise. As the toaster defrosted his hash browns, Jim counted his eyelashes and made a mental note of their quality and position.

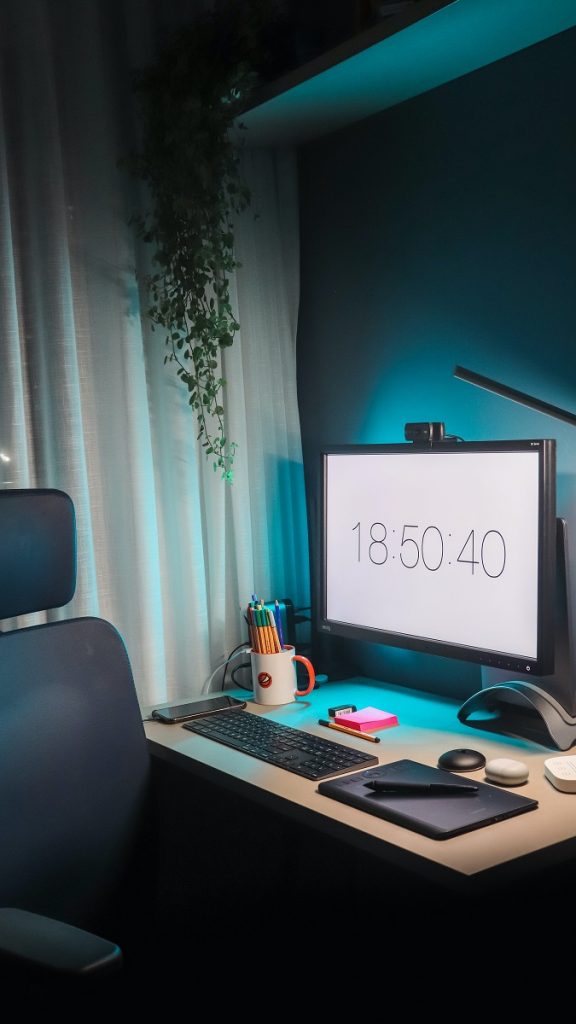

8:57am; time to head up to the office. Decoration in the room was sedate, as befitted a professional setting; there was a framed photograph of a sailboat, and a poster encouraging him to be the change that he dreamed of. Jim sank a few inches into his velveteen desk chair (virtually every surface in the house was padded, yielding agreeably to the pressure of foot or behind) and brought his computer to life. He had an unread message: his friend Derek seeking his opinion on a pair of earbuds in black. Before the mall closed down and Derek moved to Seattle, they used to evaluate the new arrivals in person. They mostly wrote messages these days. A small stack of print jobs awaited Jim’s attention; spurred on by sips of tea and the top forty hits, he considered them one by one. Shrink wrap no, saddle stitch yes, 32-pound gloss, must be delivered by Friday. He filled out the estimate sheets, noting at the bottom of each that superlative service was the company’s passion. This was generally his only contact with customers. Those who accepted were connected with the service department; those who were displeased by his proposals scoffed at the figures in private and took their catalogues elsewhere.

At ten-thirty, he exercised his right to a ten-minute break. The interval permitted him six hearty laps around the perimeter of the back gardens. He set the outdoor air filter on “Alpine” and headed north toward the Pepperville town line. (A few years earlier, it had dawned on Jim that the property wasn’t the simple sleep venue inhabited by past generations; rather, it was a town unto itself, with facilities for business and leisure, personal care and civic engagement.) Jim used to walk the block to his old high school and back, but the prospect had become less attractive: the air was full of pathogens, and the bushes were full of fiends. Just this morning the news had reported that a jogger had been dismembered in Oak Bluffs, Wyoming. Plus there wasn’t a whole lot to see; homesteads that didn’t belong to him, and therefore where he didn’t belong. Their owners would be startled to see a dogless stranger walking the streets. They existed concurrently and shared a garbage collector, but had never actually met.

Mercifully, he’d missed the mailman’s arrival. There was a small box addressed to Richard Pepper (Jim had ordered a set of rain boots on the cat’s behalf) and a letter for Marion—a credit card company offering free balance transfers and membership in the exfoliant of the month club. Jim sighed. If only she could rejuvenate her complexion. His mother had been gone five years; within months of her passing, his father had followed.

There was a notice for James Pepper from the DMV: his driver’s license was about to expire. He tore the letter into sections; as he chewed them to a workable pulp, he wondered whether renewing it was worth the ordeal. (Jim ingested all correspondence bearing his social security number. He’d shredded all of his mail until an item online advised him to give up the practice; enterprising thieves, it warned, would happily trek through landfills and paste the shreds back together.) He hadn’t driven (or left Pepperville at all) since last summer, when he rushed Richard to the vet.

Reinstalled in his desk chair, Jim ran an eye over the cheery green lights of his modem. The flashes seemed farther apart than normal—a weak pulse that sent his own through the roof. Recollections of the Great Blackout of the previous winter—sixty-three hours that followed a storm. No supplies, no news, no voices in the town but his own. He held his breath for over a minute as the light fluttered before him. Maybe he was imagining things. Several websites materialized at his command; he unclenched his stomach and threw himself back into work. The 10:41 to twelve interval was fruitful and bracing. Every so often, a message from a co-worker came in: the customer had misplaced a decimal point, his timeline was too ambitious, so-and-so wanted his textbook to bleed after all. Nearly all of the issues were resolved via email; rare was the controversy that required a verbal exchange. Disembodied, his co-workers tired him less; the removal of their throat clearing, thoughts on the weather and inebriation stories made a remarkable difference.

At 11:59 a.m., he received an email from his boss Margaret.

“Good morning, team,” it read. “I’m pleased to announce that we may be reopening the office shortly, maybe as early as Monday. We have an opportunity to rent space at the Cummings Center for a very good price. The board is reviewing the details and will make a decision this evening. Regards, M.”

The chipper lines hit him like the blow of a baseball bat; for a minute he thought he might vomit. He’d been working from Pepperville for the past three years, ever since they’d closed the office to avoid an increase in the rent.

The town had been good to him. The longer he lived there, the more its fineness impressed him, and the sharper the contrast with the perilous world beyond. Within its verdant borders, he was a man with the freedom to recline in the chair of his choice, to charbroil anything that he wanted, to paint and repaint the shutters as the yen for variety struck him. He could pipe in entertainment from the four corners of the earth; he could accomplish most errands without the need for movement or speech.

Now he was to be driven out into a noisy, unfeeling world. He descended to the restaurant district with a heavy heart, nearly falling over Richard on the stairs. In addition to the café, the district boasted a taco and salad bar, a shake counter, a ramen house and a grilling station out on the porch (there was also an indoor grill on which he theatrically cooked steaks on the weekends). Jim had spent many a pleasant half hour in this section of town; he was sous chef, busboy, and cheerful diner in one. This afternoon, however, he was too full of dread to conjure up anything new; fortunately there was leftover quiche from last night’s salute to Provence.

He would have to start getting up early again. Get used to driving again. The thought of retaking his place in the morning traffic alarmed him: what if his engine overheated and the vehicle burst into flames? Then there was the office itself. The new space, he assumed, would lamentably be like the old one. A whimsical higher-up had insisted they go open concept, with fifty employees imprisoned in one garishly-lit open room. It was supposed to promote equality and off-hours paling around, in addition to eliminating time wasted knocking on doors. In practice it meant that Jim overheard every cough and guffaw, and that there was no place to hide.

Twice a day he’d crossed the office to drink water from a paper cone. No matter how purposefully he walked, someone always intercepted him, demanding a summary of the previous weekend or a preview of the next. In Pepperville, he could rehydrate without being accosted. He remembered Cheryl, an older woman who happened by his desk practically every day and shouted, “Hey, it’s five o’clock somewhere!” There was no obvious answer to this. Sometimes he agreed, sometimes he tried to laugh, sometimes he named a place where he believed that the hour had come.

As he worked his way through the quiche, a truly terrible thought struck him: the revival of happy hour. At least one evening a week, his coworkers convened at a bar and more or less insisted he join them. A few times he’d said that his parents needed his help (in those days, this was basically true: they’d never not been old; they’d never not needed him. There was always a gutter to unblock, a prescription to retrieve, or an appliance that was making an ominous noise), but he soon found that if he made an excuse, they threatened to change the night in order to accommodate him.

The idea, Jim understood, was for him to kick up his heels in the company of friends, but the truth was that he worked more during this hour than in all of the others combined. They talked about movies he hadn’t seen, retired colleagues who were more beloved now that they weren’t around, whether Crystal Pepsi might make a comeback. Mostly it was a draining ordeal, but he did experience the odd happy minute, briefly enjoying the corn chips or a joke that somebody told. There was also a certain satisfaction in capably playing his part.

In those days, he was in practice. Conversation was like a dance, and he wasn’t a natural dancer; nevertheless, forced onto the floor so often, he’d improved enough to keep from attracting attention. With a skilled partner, he could follow, but he’d never learned how to lead. Now he’d be stumbling all over the place.

There was also Al-Shabaab to consider. He’d heard the terrorist group was gaining ground in East Africa; surely a prominent landmark like the Cummings Center would attract their attention sooner or later. His heart leapt into his throat as he ascended the stairs. (The attacks had started around the time that his parents died and had become more numerous lately. Normally Jim didn’t know what provoked them, but in this case his falling apart stood to reason). The possibilities overwhelmed him: radon in the new office, arsenic in the coffee. Tire slashing, flash floods, the slim but very real chance that he could slip and fall out a window (like that woman he’d read about).

Painfully, the projects kept rolling in. How could he think about bindings when he was under siege? A message from a colleague came through; he’d estimated a job at five dollars instead of five thousand. A ray of hope pierced the gloom: maybe he could get fired! Luxuriate in the café, spend every day in the gardens discussing the classics with Richard. The dream petered out on closer examination. Without a salary coming in, how would he maintain the town? Plus after twenty-odd years of precision, demonstrating incompetence would require a very grand gesture.

He was briefly uplifted by the afternoon’s arrivals: his weekly groceries, a ceramic bonsai tree for the office, a pillow sham he’d ordered for Richard’s bed. Each new item that he welcomed into the town changed his life completely, at least for a couple of days. On this occasion, his excitement was laced with sorrow; already they seemed like the relics of a magnificent lost civilization.

He’d be a visitor from now on: a tourist who never stayed long enough to benefit from what Pepperville had to offer. The evenings and the weekends: brief vacations from his torment, never long enough to revive him. Every day would be like a walk through a treeless field during a lightning storm; he’d return with enough energy to reheat a soup and maybe remove his shoes before he lost consciousness.

Jim sat with his head in his hands, wishing away the minutes and yet trying to savor them (this being his last chance to work unobstructed). Five o’clock came and released him. His first thought was to bury himself in his bathrobe, but then he remembered the trip. India! He’d had his eye on the country for months. He was in no condition to travel; on the other hand, it might distract him from his impending misfortune.

He changed into something stylish, topping things off with the belt (Jim always tried to look his best whenever he was abroad). He went downstairs to the theater district and tried to locate the remote. When the local movie theater closed down, he’d invested in a professional screen, burgundy curtains and a top-of-the-line recliner. He had a second recliner for the rare night when Richard joined him. Jim had invited him along on this evening’s excursion, but the cat hadn’t shown much interest; he was a homebody by nature.

The trip began with a rousing concert in front of the Taj Mahal. How lovely to take in the splendor without fear of being beheaded. Ethnic hostility, malaria, stampedes—through the wonder of displacement-free travel, Jim circumvented them all. He’d visited much of the world in this way. There was a group of young medical students enjoying the show along with him; after the music ended, they proceeded to a series of hotspots: gardens, glittering tombs, ragged restaurants that tourists missed as a rule. Jim accompanied them on these outings like a spirited chaperone. How warmly they spoke, how skillfully they sang and danced, how hospitably they welcomed a stranger!

The girl in the purple sari reminded him of Amy, a friend of Derek’s who’d briefly been his girlfriend. He was happy with her, going on long drives and holding her waist as they walked, but a few months after they met, she accepted a job in Chicago and the romance died out over the miles. He’d heard she had three children with somebody else.

When two of the students got married, Jim partook in the banquet, ordering similar-looking dishes from New Delhi Delight on his phone. (When it came to cuisine, he always followed the lead of the locals). By the next toast, the stapled white bag had appeared on the welcome mat (on the delivery application, he’d checked “Leave on doorstep and scram”).

As the reception dragged on, Jim began to feel weary. The diversion had done him good, but the facts were the facts: no amount of birdsong or perfumed rice would make him any less doomed. He turned off the movie and shambled upstairs, checking the phone for any word from his boss. The main office was on the west coast; they’d still be working out the details of his demise.

Jim wished he had someone to talk to. He missed his parents’ quiet counsel; he missed Derek (he would still be at work; he was always at work). Anyway they never talked about this sort of thing. They talked about Derek’s investments, the pros and cons of their workouts, which of their devices might benefit from an upgrade.

He wondered if he should have tried to repopulate the town after his parents died. Meeting people in the area was difficult unless you had children or an addiction to break the ice. Theoretically, he could make the hour’s drive from Pepperville to the city. In New York, he’d heard, people his age met up to taste wines and kick off new friendships. This was out since Jim didn’t drink; all alcohol tasted the same to him and reminded him of the stuff his mother used to spray on the stove. He wasn’t the sort of man who could play Parchesi or learn to tango with strangers; the prospect of arriving at bar unannounced, without the pretext of print jobs to discuss, simply exhausted him. Plus who could you trust these days? Anyone he met might drive him over a cliff, try to plant drugs on his person, or recruit him into a youth gang.

He’d become friends with Derek largely because there was no choice; they slept ten feet apart in the freshman dorm. The friendship had built up gradually, like sediment in a pipe. Eventually, questions like “Have you seen my comb?” and “Is it cold in here, or is it me?” gave way to more elaborate conversations.

Jim went up to the leisure district and threw himself on the couch. Familiarity was what was required. In Derek’s absence, he’d found himself a new crowd. He turned to the channel where he knew he would find them.

The four women sat at the kitchen table, savoring tea and a gentle joke. He’d come to think of himself as a fifth Golden Girl, enjoying cakes in his robe and laughing along with them. Of course the ladies couldn’t advise him directly, but the voices relieved him. Whatever happened, they’d be there—a soothing presence to rest in.

A week, a month, six months from now, they would be their genial selves, but what sort of a wreck would he be? He pictured himself going downhill at dramatic speed, like a president during wartime. Even if nothing killed him outright, the daily threats would erode him: he’d grow weaker, more distraught, until he was helpless in the face of any of it. Unable to do his job, unable to manage the town. Returning to work or refusing would take him to the same place. There was no way out.

The cozy kitchen went blurry as his eyes filled with tears.

The sound of a cowbell sprang from his phone; a message had come through. Jim reached for it without thinking.

“Bad news, people,” Margaret wrote. “We couldn’t work out the logistics, so the deal fell through. We’ll keep working remotely for the time being. Hope everyone has a good weekend.”

Stunned, Jim briefly cried harder; then he started to laugh. A good weekend? A sparkling chain of horror-free days stretched before him; he would revel in every second. He looked at the TV with gratitude. Now he could join the party! He couldn’t help but wonder if they’d made it happen somehow.

Keyed up as he was, he decided not to wake Richard. Tomorrow the two of them could celebrate in earnest, with caramel sundaes and a marathon of Murder, She Wrote. Jim readied himself for bed, depleted from the day’s exertions. He set the security system on “Terminate” and lay down on the floor. (He’d taken to sleeping on the carpet below the window line; drive-by shootings were on the rise nationwide). He marveled at his good fortune. To be allowed to remain, to carry on running the town and basking in all of its splendors. Protected, body and mind, in a peace where no one could reach him.