By Eric D. Lehman

The hobo arrived at Mark Twain’s house at sunset. Sun rays slanted across the tumbling creek and ancient elms. The large house was reddish brick, adorned with at least four chimneys, a wraparound porch, and a steep roof. Flowers bloomed in the garden, even though many he had seen on the road had wilted with the summer heat. He noted the clean windows, the absence of horse dung, and the deep ruts of heavy carriages on the gravel drive.

He knew this was the home of the famous author; in fact, The Innocents Abroad and Roughing It were the only two books he had read in the past decade. He had once been more of a reader, that’s true—he had even fancied in his youth that he might write stories like James Fenimore Cooper or essays like Ralph Waldo Emerson. It was the works of these two men, he thought half-bitterly, half-happily, who had ruined him. When his classmates had worked on their sums or grammar, he had dreamed of roaming the forests of early America with Natty Bumpo, practicing self-reliance like Emerson preached. And then when he had not gotten into Yale or Harvard, he had taken to the road instead, telling his disappointed parents that he was joining a New London customs house, but instead heading out into the forests to live off the land.

That had lasted all of three days before he was begging for scraps from an Eastern Connecticut poor house. You couldn’t be a gentleman wanderer in New England anymore, he told himself, but the real reason was that he wasn’t prepared. To his credit, he then worked for nearly a decade on the edges of the 1840s civilization, learning to fish and hunt and camp. It was during this period that he had met Henry David Thoreau, who was living his years in a small cabin at Walden Pond. The hobo…Jed he called himself by then…had gotten involved in an ice-cutting operation at Walden. After missing his train, he met a short, bearded man on the path by the pond and had spent a few hours together. Thoreau taught him a surveyor’s trick to wayfinding that he had used on his travels ever since.

It wasn’t until years later that he realized whom he had met, and it was that realization, so to speak, that had given him the bug to meet other famous writers and artists. Better yet, he found that a crowd of disciples, usually aspirant writers themselves, gathered around these celebrities. These followers were easy to touch for money and food, particularly when he lied about his past, making up fantastic stories about fighting grizzlies and hunting whales, playing deadly card games with cowboys or smoking hasheesh with pashas in the Orient. The hangers-on were greedy for stories like that, and happy that they had hit the vein of gold that would make them rich and famous, too. He found that he was good at lying, good at feeding peoples’ desires and dreams, as Cooper and Emerson had fed his own.

In the nearly three decades he had worked this little swindle, none of these aspiring writers had become famous themselves. Until now, that is. He had met Samuel Clemens out in California, told his usual balderdash, and one of those stories…or a variation of it…had appeared in Roughing It. And now, ten years later, he had arrived on Clemens’ doorstep, in order to collect the debt.

He stepped under the red portico and rang the bell. A tall man in a smartly outfitted butler’s uniform opened the large, heavy door. “Yes?”

“I’m an old friend of Sam’s from California,” he began. “Just stopping by on my way to Boston. If Sam’s here, I just thought I would say hello.”

“May I give your name?”

“Yes, it’s Jed Bond. I’m sorry I have clean run out of calling cards.”

The butler looked him up and down, unimpressed with the tattered clothes and greasy beard, perhaps. “Please wait here. I will see if he is available.”

The hobo had seen him on the balcony from a distance, or a man with a large mustache anyway, and knew that he must be home. “I know he’s here and he’ll be glad to see me,” Jed said quickly before the servant closed the door. “I have a copy of this here book, Roughing It, which I know he’ll want to sign, since I helped him write it, so to speak.”

“Indeed?”

“Just one chapter,” he said modestly. “That story about Tom Quartz the miner’s cat.”

“Is that so? Well, I will let him know,” said the butler, firmly shutting the door.

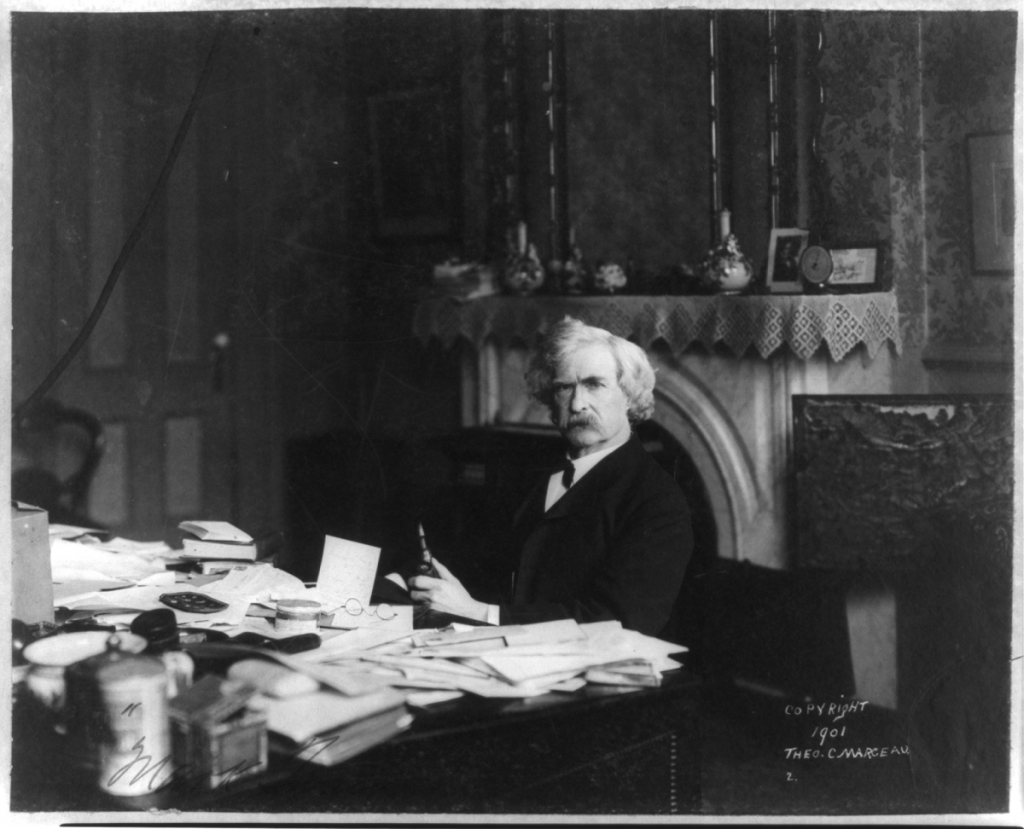

Jed began to think out his next move, but the man returned. “This way, sir.” He led Jed through the foyer, full of carved wood and glass. He looked up in astonishment. One impossibly thin, twirling pillar seemed to hold up the three-level staircase. It was the grandest author house he had ever seen, surely. His wife must be rich. Plans began to bounce off the inside of his skull. This could be a greater humbug than all the others. Never before had he had an inside track to the author himself, the real one, not the disciples. Before this, he had encountered many authors, but had never been invited into their library. Never had more than a few kind words at a lecture-hall book signing or a few curse words at the back door.

He could hear the laughter of children somewhere in the house. It was an unusually warm summer night, but cool here, curtains closed on the west. The fountain in the adjoining conservatory burbled merrily and he felt the rich, thick rug through his thin boot soles. The room held brass andirons, marble sculptures, heavy carved chairs with plush seats, and glass lamps. Books lined the walls, an author’s books. Maybe some by the man himself.

Despite all this luxury, he did not feel particularly out of place, even in his tattered travel-stained clothes. He had steeled himself against such social niceties in the past. Besides, he knew what kind of low-born swindler Clemens used to be. They were the same; one had simply found a honeypot.

He examined a painting of a country scene with a campfire in the forest that hung on the wall. At those sorts of fires, he had met a thousand other tramps over the past three decades. They were not all the same: some were seekers, genuine religious folks. Some were seeking something else, usually the bottom of a bottle of gin. A good number were like him, though, tellers of tales. Sitting around a campfire like the one in the painting, he had heard a million stories, ones that he had promptly taken as his own, embellished when necessary, and passed on. But many of these folks did not have the knack for it. One in twenty did, perhaps. He was one of those. His childhood dream came back to him, a hope lifting in his heart. Could he own a library like this? A house? A wife and children might be too much to ask for certainly, but…

“Nice painting, isn’t it?” A voice at his elbow spoke, making him jump. It was Clemens himself, who had somehow sidled up noiselessly from some adjoining room. “This painting now, of a sunset, Livy bought it cheap at an auction in Meriden.”

Sunset? Jed was sure it was a campfire. “Mr. Clemens, ah…” he began.

“Jed, don’t you dare call me anything but Sam. We go way back, you and I, and there’s no need to stand on ceremony.”

“Thanks…thank you– ” Jed grabbed the man’s hand. “I was just in the neighborhood…”

“Nook Farm is quite the neighborhood, don’t you think? Harriet Beecher Stowe lives right next door, did you know that? Most famous author in America…or she was!” he said, preening a bit. It was after dinner, but he was dressed in a suit and tie, gold watch chain hanging from one pocket and a silk handkerchief in the other. If Jed hadn’t known the man from before, he would have thought him a railroad baron or Congressman.

“Ha, ha, yes, I’ve read the Innocents Abroad. Quite the tale and I hear it is doing quite well.”

“True! All true…except for the parts I made up, of course. But the story’s got to have the ring of truth amidst all the fooleries, don’t you think?”

“Yes, I do…Sam.” Jed firmly said the author’s name. “It’s been too long, Sam, I just wanted to say hello, maybe…”

“Oh, we must do more than that!” Clemens looked around as if making sure no one was listening. “Come, my good sir, men like us should not trouble the ladies of the house with our idle chat. Would you like to join me for a meal and a drink…or two?” He winked. “There we can talk about the old days in California and perhaps brew a few new stories to tell.”

“That sounds good,” Jed began. “I wonder…”

“Would you like a cigar to smoke as we go? Wrapped in leaf from just up the road here, don’t you know.”

“I usually smoke a pipe.”

“Why then, here you go.” He handed Jed a small pouch of tobacco. “Finest Virginny, that is. Say…” he drew the hobo close conspiratorially. “I have to thank you. I don’t usually get to have my evening smoke. Livy is dead set against it.”

The author kept up a steady stream of talk all the way into downtown Hartford. Jed got a few words in, but let the man go on and on. He was clearly desperate for companionship. After all, that was everything Jed wanted—a long talk, a chance to worm his way in, and then another meeting, and another… But things were moving so fast that he couldn’t even make the play. Clemens tumbled out with gift after gift. “Say, I bet you got some peachy stories from your own travels,” he said at one point. “What if I put you in touch with my publishers?”

At last, they reached the main square of Hartford, with its large, pillared houses, state house, and art museum. Carriages rumbled by led by blinkered horses, while top-hatted businessmen strolled together with women in bustled dresses along the avenues.

“Let’s see, where shall we take our sup?” Clemens asked. “One of these fancy establishments?” He pointed down a row of gilt-fronted hotels.

“Isn’t there someplace a little more our style? I know you live a great big mansion now, but…”

“You’re right,” Clemens tapped the side of his nose. “I know just the place. Honiss Oyster House.” He led the way down towards the river. The rougher neighborhood near the Oyster House was familiar territory to Jed, and it seemed to Clemens, as well. He appeared to have dropped a decade in age and his arms and legs seemed looser, more natural. Jed could feel him getting closer to him in character. And that was the great man’s weakness, perhaps. That was where Jed would find the heart string and pull, pull until they were bound together. Who knows where that could lead?

Inside, thick smoke hung in the air and plates of quivering oysters, bread, and cider shuffled around the room, held by deft sailors.

“Best oysters I’ve had on the east coast, at least, better than in Europe by a long pull. Did you know that Abraham Lincoln ate fried oysters when he campaigned here? That’s the story anyway, became his favorite dish in the White House, and everything. Healthful, sure.”

“I had my first oysters in Connecticut, too. Grew up around here, actually.”

“Well! And to think we met in California.” Clemens twirled his mustache and waved a hand to someone at the bar. “I am just so darn excited to see you, Jed.” He checked his pocket watch. “We have plenty of time, plenty of time to eat our fill.” He winked again. “And drink it, too.” Huge mugs of cider sloshed onto the rickety wooden table. “Now, I want to hear all about what you’ve been doing these ten years, but first, I just have to introduce you to Jimmy, the oyster shucker here. Jimmy, show my friend what you are doing with those hands of yours.”

Jimmy, a huge man with an apron and missing teeth, spread two meaty palms wide, his fingers lined and scarred with a web of ancient cuts.

“See, Jimmy’s trade depends on his hands. And yet, those hands are just what suffer from it the most.”

“Can’t smell much, neither,” said Jimmy.

“He can’t smell! Did you hear that, Jed? From the vapors, perhaps, of the sea. Supposed to be healthful, though, isn’t it? Have you spent much time at sea? No? Well, let me tell you…” Clemens launched into a retelling of the ocean voyage of the Quaker City in the The Innocents Abroad, but this time with more interesting and more unprintable anecdotes. Soon a small crowd had gathered around him, roaring with laughter. Jed finished his cider, and another, waiting his turn, waiting for the chance to spin a yarn.

His turn never came. He woke in the hazy pre-dawn dark. Clemens was gone and so was almost everyone else. A few others lay asleep on the benches of the tavern. Jed stood up unsteadily and peeked out the door at the silent Hartford streets. The first hints of dawn glimmered in the east and a train whistle sounded in the distance. He shook his head to clear it and tried to think. He would take a room in a flophouse, perhaps, and continue his plan. Clemens clearly liked him, took him to dinner, supplied him with cider…

Suddenly suspicious, he blearily looked back inside the Oyster House. Just then a huge, meaty hand enveloped his shoulder.

“Good morning, sleepyhead.”

It was Jimmy, the oyster shucker. The other hand brandished a small, sharp knife, and he scraped his teeth with it. “We’re going to take a little walk now.”

“What’s that?” Jed found himself propelled along the street by the large man. In his youth he might have considered evading him, slipping into an alley, or even starting a fight. But he was no beardless youngster, and he helplessly revolved his legs, trying to keep up and not spill onto the packed earth of the road.

“Where are we going?”

“You’ll see.”

It didn’t take long before they reached the docks, where a large steamboat with City of Hartford painted on the side was just getting a good fire going. Seagulls and starlings fought over scraps in the shallows. Jed was surprised to see a good number of people already on the deck with parasols and pince-nez, and more arriving from the city streets.

“Sir, I am a friend of Mr. Samuel Clemens…”

“Oh, I know!” Jimmy cut him off with a grin. “Best friends to get a free meal and passage to New York. Wish I was better friends with him.”

“I have luggage at the Union Hall Hotel.”

“Naw, that’s a tall tale if I ever heard one, And I heard plenty from your friend Sam Clemens.” The large oyster shucker shoved him unrelentingly onto the steamboat deck, handing the deck officer a small wallet. Still feeling the effects of the night’s revels, the hobo collapsed near the railing and was sick over the side. The other passengers moved away and continued to avoid him as he sat there holding onto the brass, his legs hanging limply in the air. Arms folded, Jimmy watched from the dock as the large paddlewheel began to revolve, and the steamboat chugged away from the city and down the Connecticut River.

As the boat steamed its way past the entrance to Wethersfield Cove and curved toward the east, the hobo began to see the humor in it. He stood up and laughed aloud, cackling to himself, and stuffed his small clay pipe with Clemens’ fine tobacco. The other passengers moved further along and muttered. The deck officer sauntered over.

“Don’t try any funny business, sir. I have my eye on you until we get to Manhattan.”

“Funny business!” Jed cackled. “Indeed, you have nothing to worry from me, good sir.” He offered the man a pinch of tobacco, and after a moment he took it.

“Do you know whose leaf that is that you are about to smoke?” he asked the officer. “Tis the tobacco of one Mark Twain, most famous writer in America. And I talked to him all last evening.”

“He’s hardly famous,” said the man, striking a match and lighting his own stubby clay pipe. “He’s been on my boat plenty, and his children, too.”

“Ah, but he is a great teller of tales. Perhaps the greatest.”

“Is that so?” The man looked at him shrewdly. “He’s no dummy, I will grant you that. After all, you’re not the first fella he’s gotten rid of in this way. Now, unless you want to get kicked over the side into the soup, step into the smoking cabin. We’ll be in New York by nightfall.”

The hobo laughed again. It was a good joke on him. When he told it, later, to other tramps, the rube would be someone else. He would make it even funnier, perhaps. But he finally understood that he was only an amateur, a dabbler in the art. A great story was only part of the equation. A great storyteller was needed, too.

“Don’t worry, sir, I have learned not to trifle with riverboat pilots,” he said as the officer hustled him into the cabin. “They know all the shoals and snags.”

Eric D. Lehman is the author of 22 books of fiction, travel, and history, including 9 Lupine Road, New England Nature, Homegrown Terror: Benedict Arnold and the Burning of New London, and Becoming Tom Thumb: Charles Stratton, P.T. Barnum, and the Dawn of American Celebrity, which won the Henry Russell Hitchcock Award from the Victorian Society of America and was chosen as one of the American Library Association’s outstanding university press books of the year. His novella, Shadows of Paris was a finalist for the 2016 Connecticut Book Award, a silver medalist in the Foreword Review’s Independent Book Awards, and won the novella of the year from the Next Generation Indie Book Awards.