By Dan Geddes

“A typical Altman film is less a movie to watch than a kind of a place to be in; I think that as a director he likes to be a visitor to the place where his characters are interacting.” — David Sterritt

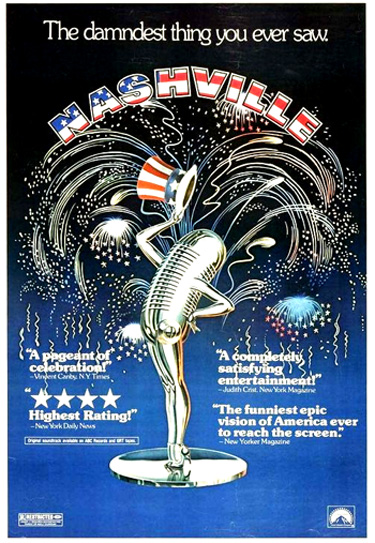

Robert Altman’s Nashville (1975) is one of those divisive classics, spawning defenders and detractors in its wake. It’s certainly not a movie that you would recommend to everyone, but maybe to film students and afficionados, and not even all them will like it. Nashville is a slow-moving 2 hours and 40 minutes, and a solid hour of it is music. Country music. Sometimes it feels more like a music documentary than a Hollywood feature. Because the characters are fictitious, and many of the songs were written by the actors who play them, Nashville also has a mockumentary feeling. The opening title sequence, featuring an exaggerated TV style pitch for the movie itself, frames the movie as a satire or a mockumentary. But like a lot of satire, Nashville is not particularly funny; it’s serious business.

The most striking thing about Nashville is its unusual, Altman-esque, narrative approach. These are four days in the life of 24 characters, whose lives are intertwined in ways they do not understand; characters who love to talk over each other rather than listen to each other. You see their strivings, their affairs, and how their different social circles overlap in ways that they don’t see.

Altman related in his DVD commentary on Nashville that his approach was to create events for his actors to move around in, always staying in character, often improvising, not knowing when the camera was on them. Into these events—Barbara Jean’s (Ronee Blakely) return from the airport, the extended traffic jam on the highway, Haven Hamilton’s (Henry Gibson) party, the many musical performances, and political events—the actors were thrown, microphoned (using new recording techniques), and let loose into the event with instructions for what the scene was intended to accomplish for his or her character. This produced an abundance of natural-sounding overlapping dialogue, for which Altman’s films are known. The British Academy of Film and Television Arts gave its BAFTA Award for Sound to Nashville.

One theme of Nashville is the multiplicity of forms of communication, including communication that doesn’t land. As Hal Philip Walker’s colorful campaign van creeps through the city barking out half-crazy political platitudes via its ominous mounted loudspeaker, and we have the sense that no one is listening. Hal Philip Walker himself is never seen. Linnea (Lily Tomlin) communicates with her deaf children via sign language, which her husband, Delbert (Ned Beatty), hasn’t learned, and so can’t communicate with his children. As Tom Frank (Keith Carradine) sings “I’m Easy” in a café, the camera cuts between women in the audience he has slept with (Mary, Opal), plus groupie L.A. Joan, and Linnea, sitting in the back, the woman he will bed that night. At Haven’s party, Buddy Hamilton, Haven’s son, who wanted to become a singer rather than a lawyer, quietly sings a heartfelt song he wrote to Opal, who abandons listening to him in mid-song, so she can gawk at Elliot Gould, who just arrived at the party. During a daytime concert Barbara Jean degenerates into a clearly insane random babbling, suggesting that her recent visit to a hospital was due to mental issues.

Is Nashville a satire? I keep wanting to write “Nashville isn’t a satire; it uses satirical techniques in places,” but upon reflection that isn’t a fair assessment. Much of Nashville is clearly satirical. The counterpoint is that the movie also has sincere, unironic scenes that make you feel, and show you what it is like to be human and fallible. Even if not always satirical, some of these scenes feel cynical: they are showing you to be human is to be vain, conceited, obsessed with one’s image, aspiring to be a star even in the face of common sense. Clearly satirical elements can be found in abundance: the cold opening TV commercial parody opening sequence; Haven Hamilton’s patriotic, bi-centennial, title-credit song (“We must be something right to last two hundred years!”), as well as Hamiton’s other songs; the entire Hal Philip Walker campaign, delivered in earnest, plays as political satire.

Other things play cynically, or with a jaundiced eye: Sueleen represents a talentless wannabee, willing even to strip off her clothes for the chance to be a star; Wade, a waiter friend of shouts to black country musician, Tommy Brown, that he is an Oreo cookie (black on the outside, white on the inside). Opal’s hyperbolic monologues play as a parody of a gushing broadcast journalist, but does she really work for the BBC? Shelley Duvall’s L.A. Joan is one-dimensional, only hovering after any single man in her view, not even bothering to say good-bye to her dying aunt, much to the distress of her uncle, Mr. Green. L.A. Joan’s star-struck superficiality is distressing, as is Tom, the self-obsessed single-songwriter, playing only his own songs while lounging in his hotel room, only looking for the next woman to hook up with.

The music itself takes center stage in the movie. Because most of the songs are not satirical or ironic, even if the lyrics sometimes seem trite (as country music may sound to many). Nashville doesn’t try to be a comprehensive view of the country/western scene, but instead offers a series of emblematic and overlapping sketches. The full music numbers are among the most sustained scenes. Other scenes feel truncated, not only due their relative brevity, but also because of the editing. The camera jumps us through many crowd scenes, landing us on unlikely snatches of conversation, where characters from other circles are seen in the background, giving the viewer the “aha” moment as we see the social circles collide and we see how the characters’ lives overlap in ways they themselves do not see. This is a special quality of Nashville (and other Altman films) that we don’t see in most feature films.

Hal Philip Walker’s final campaign rally has an ominous feel. Assassin Kenny Fraiser has been walking around town with a violin case he never opens, and it would appear that he’s planning to kill the Presidential candidate, Hal Philip Walker. Why does he kill Barbara Jean? Because he thinks she “sold out” by singing at Walker’s rally? (At one concert he cried while watching Barbara Jean sing.) Because the celebrity is on some level more powerful and iconic than the politician? It’s not clear, but maybe it doesn’t need to be; maybe the movie isn’t trying to make Kenny’s motive clear. Kenny Frasier is now seen as a prophetic precursor to the man known for shooting John Lennon, Mark David Chapman. Barbara Jean’s on-stage assassination is shocking. But Altman doesn’t leave us shocked and saddened. In the confusion, as a bloodied Haven helps carry the mortally wounded Barbara Jean off-stage, he asks someone/anybody to sing, and Wilfrid aka “Albuquerque” (Barbara Harris) steps into the moment, like an understudy replacing the lead. She finds the wherewithal to sing the hit song “It Don’t Worry Me” to the stunned audience. (The show must go on. The Queen is Dead / Long Live the Queen.) The lyrics capture this post-Vietnam and Watergate moment in US history: “You might say that I ain’t free / But it don’t worry me” (somehow echoing the line in “Sweet Home Alabama”: “Watergate does not bother me.”).

It is understandable that many people don’t enjoy this movie and find it extremely over-rated. It’s long. There’s a lot of country music. The storylines, thin and non-conventional as they are, can be difficult to identify let alone to follow. Others may find the attitude toward the country/western scene of the 1970s to be reductive or condescending. The seemingly loose style of filmmaking may seem lazy or careless. Is it ironic, or isn’t it? The assassination of the virginal Barbara Jean may seem unbelievable or gratuitous. You may detect the hands of the director tacking on a big, symbolic death at the end to give the picture meaning (a charge one can also make against the deaths in Altman’s later character ensemble, Short Cuts (1993)). Maybe you are too aware of a director who may be looking down upon some of his characters.

On the plus side, Nashville offers a singular movie experience. The improvised dialogue and scenes feel real. So does the relative lack of narrative artifice (no obvious three act story arc, just four days in the life, punctuated by a surprise climax). Filmed in the summer of 1974, as Nixon resigned, some will appreciate it for its 1970s nostalgia value alone. You get to see a bevy of budding stars in their youthful prime: Lily Tomlin, Karen Black, Jeff Goldblum, Shelley Duvall, Ned Beatty, etc. The best of the music, especially from Ronee Blakely, Karen Black, and Keith Carradine makes the movie a credible musical, and gives it a greater impetus for repeat viewings.

References

https://www.filmsite.org/nash.html “Nashville” — FilmSite ranks it as one of its top 100 movies of all time. This long article on Nashville includes a useful, comprehensive summary of the action of the film.

https://cinemontage.org/robert-altman/ “Robert Altman: The Sound Crew’s Best Companion” covers Altman’s ground-breaking audio techniques.