Review By Dan Geddes

See also reviews of Kill Bill and Kill Bill 2 and also Tarantino satires: Harder and Scent of a Banknote.

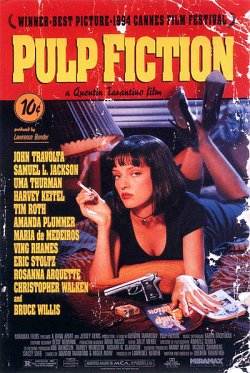

Directed by Quentin Tarantino

Written by Quentin Tarantino & Roger Avary

Cast

Tim Roth…. Pumpkin (Ringo)

Amanda Plummer…. Honey Bunny (Yolanda)

Laura Lovelace…. Waitress

John Travolta…. Vincent Vega

Samuel L. Jackson…. Jules Winnfield

Phil LaMarr…. Marvin

Frank Whaley…. Brett

Burr Steers…. Roger

Bruce Willis…. Butch Coolidge

Ving Rhames…. Marsellus Wallace

Paul Calderon…. Paul

Bronagh Gallagher…. Trudi

Rosanna Arquette…. Jody

Eric Stoltz…. Lance

Uma Thurman…. Mia Wallace

Spoiler Alert: This review assumes you have seen Pulp Fiction.

Love it or hate it, and most people love it, Pulp Fiction was probably the most influential movie made in the 1990s. And its influence persists. It opened up a lot of new territory, especially in putting comedy-of-manners dialogue in the mouths of killers and other moral degenerates. Pulp Fiction was so hip and cool when it came out in 1994, it inspired countless imitators, and influenced other great movie-makers.

This essay discusses: the use of violence; the comic dialogue, and the structure of Pulp Fiction.

Violence in Broad Daylight

Perhaps a secret to the impact of Pulp Fiction is that most of the violence takes place in broad daylight. Most of the violent scenes take place during the day:

- Pumpkin and Honey Bunny’s restaurant hold-up;

- Jules and Vincent’s killing of the young drug-dealers in the apartment;

- Vincent’s shooting of Marvin in the back seat of the car and subsequent clean-up at Jimmy and Bonnie’s house;

- Butch’s killing of Vincent;

- Butch’s scenes with Marsellus and Zed.

As we watch hit-men and mobsters and stick-up artists move through their familiar LA suburban world without fear of police—or of anything—our own terror is heightened. Suburban America suddenly seems vulnerable to the violent acts of smooth-talking, pop-savvy contract killers.

There are really not that many deaths in Pulp Fiction, but the aura of violence is ever-present. The violence is handled effectively. For example, Vincent is killed, having been caught off-guard, while engaged in the very human act of taking a shit. But of course, it’s a plot device, because bad things happen every time Vincent goes to the bathroom.

The most disturbing scene is when Vincent must stab Mia in the heart with a hypodermic needle to resuscitate her after an overdose. I literally winced and turned away confronted with seeing such an act, despite having watched slasher movies since the age of nine—when a character is alive on the screen we care. Reputedly, this scene was shot in reverse; Travolta pulled the needle away from Thurman and the shot was reversed.

Another way the aura of violence is created is that the characters talk about acts of violence that we don’t see. For example, Vincent speaks with both Jules and later with Mia about the Samoan guy being pushed out a window for giving Mia a foot massage. Or we hear about Butch killing a man in the ring, which we don’t see. Or again: the fact that Wolf writes down everyone’s names when he hears of Jules and Vincent’s problems suggests the possibility of him just killing them all to solve the problem.

All this daytime violence has a surreal impact. Pumpkin and Honey Bunny hold up a coffee shop, a place where suburbanites normally feel safe. Jules and Vincent calmly dispatch four or five college students at 7:30 in the morning. Then they casually talk about whether or not it was a miracle that they were not shot. Shortly after, Vincent shoots Marvin in the car, and they drive around in broad daylight with blood all over their windshield. They drive to Jimmy’s, where they stand outside covered in blood while Winston the Wolf hoses all the blood off their bodies.

Later, Butch shoots Vincent in his own bathroom in the morning, and then tries to run down Marsellus in broad daylight. As they stagger around the suburban intersection covered with blood, Marsellus thinks nothing of drawing his gun and firing on Butch, but hits an innocent woman to the horror of on-lookers. Butch and Marsellus end up in a pawn shop, where the owner takes them prisoner to sexually abuse them and perhaps kill them after.

This violence punctuates our sense of suburban safety. Most crime-genre movies take place in urban, nocturnal settings; Pulp Fiction takes place largely in suburban daylight.

The few night scenes are romantic interludes: Vincent’s date with Mia Wallace (which though not violent is still disturbing) and Butch’s dialogues with the lady cab driver and with his girlfriend, after his boxing match.

All three segments suggest imminent or possible violence. The first titled sequence “Vincent Vega and Marsellus Wallace’s Wife” (after the two violent scenes preceding the titled sequences) fills us with the fear that Vincent will sleep with Mia and thus be caught and executed by Marsellus. The fact that other events occur which themselves are shocking is a plus, because the unexpected happens.

The audience knows that the characters will make the wrong decision, so there is a sense of impending doom, followed by a surreally horrible nightmare come true. When Vincent tells himself in the bathroom that he will just have one drink and go home, we fear that he won’t do that, and the fact that he tells himself this makes it very effective. When he says “Home” it sounds so peaceful and uneventful that we know we won’t see him get there; meanwhile Mia undresses herself (just for comfort, not necessarily to seduce him but we don’t know that). Instead, she vomits up the $5 milkshake. (Of course it’s ironic that Vincent thinks it’s so expensive when previously we saw him with a massive wad of cash, and willing to pay $1500 for heroin).

While Vincent drives Mia to Lance’s we fear she will die and Marsellus will kill Vincent. When they’re there we feel the dealer’s frenzy that he will be caught with a dead body. He’s trying to keep quiet and Vincent simply crashes the car into the front yard in the middle of the night.

Again, the threat of violence is there even in quieter moments. Vincent and Butch see each other early in the movie, at Marsellus’ club, and Butch’s lingering stare at Vincent for insulting him makes us think that Butch is a stupid boxer who will later be killed by the more violent hit man. Instead, the opposite happens

The audience experiences an even greater feeling of impending doom in the second sequence, “The Gold Watch”. The most surprising thing about “The Gold Watch” is that we the taste of fatality about each bad decision. We fear that Butch will be killed for such misjudgment. As soon as he wins the fight he was paid to fix for Marsellus he is on the run. They might simply shoot him. Or the cab driver might give him away. Or his brother’s bookies won’t pay out.

The next morning, he is afraid when waking up to the violent movie his girl has on early in the morning. The fact that she forgot to pack the gold watch, makes us feel the perhaps fatal consequences of minor mistakes (in this cinematic world). I can hardly believe he went back to get it. We know from previous movie-going that there must be a hit man at the apartment waiting for him.

But Butch proves to be a survivor, taking a circuitous route to his apartment (a great tracking shot through a seemingly serene suburban neighborhood). Butch is unbelievably lucky that Vincent is in the bathroom when he enters, but still I was shocked that he first stuck around to make himself a toaster treat—I would have beat it out of there. I guess it’s the ultimate product placement for Pop Tarts that Butch would eat one even with his life in danger.

Of course, another preposterous coincidence is that he sees Marsellus on the street. And it’s something more of a coincidence that the store he happens to duck into is run by a shotgun bearing pervert with that absurd black clad creature locked inside. But again, we feel suspense again that Butch will make a mistake, like going back to free Marsellus whom we believe may simply kill him once free. But black comedy that it is, Butch, after all he’s been through, asks his Fabienne how her pancakes were, like it’s the most important thing.

In the “Bonnie Situation,” after Vincent shoots Marvin. We experience the suspense that Vincent and Jules will be caught by the police driving around in a bloody car; and later that Bonnie will come home to the fear of impending violence as soon as we know that the robbers will inevitably confront the hit men. And on intra-scene level, the suspense that Vincent might come out of the bathroom blasting away.

Comic Dialog

Pulp Fiction’s greatest strength is its comic dialog. It’s a 2 1/2 hour talkathon, punctuated by 10 or so violent acts and an ever-present threat of violence. But the violence does pause and we are spared the spooky music that normally turns the screws on its viewers for the duration. Instead, we hear mainly mellow 70s music between and during the violent interlude.

The retro music and culturally-savvy dialog makes Pulp Fiction a comedy of manners as much as anything else, punctuated with cartoon violence to rivet your attention. Much of the clever dialog shows obsession with cultural minutiae, including brand name products. For example, Vincent famously tells Jules that in Paris you can’t buy a McDonald’s Quarter Pounder with Cheese; it’s called a Royale with Cheese. Or Lance, the heroin dealer (Eric Stoltz), states he’s willing to “take the Pepsi challenge,” i.e., a taste test, to show he can taste the difference between his $500 heroin and his $300 heroin.

Vincent and Jules also discuss social mores, such as whether massaging a woman’s feet is really sexual or not. Vincent tells Lance that he finds it “against all the rules” that a man would key his car.

Butch shows a sense of honor, both by risking his life to return for his father’s gold watch, but also to save Marsellus from his captors, even though Marsellus wants to kill him.

We are shown criminal elements of society: hit men, a drug dealer, a boxer who fixes fights, and their women. They all come across so real because of their idiosyncratic and surprisingly intelligent speech.

Jules, the hit man, reaches levels of profundity and is so chillingly calm under pressure. We don’t usually think of hit men as wanting to quit it all and “walk the earth” as does Jules (Samuel L. Jackson). Vincent, the Travolta character, shows some flashes of intelligence, as does Mia, Marsellus’ wife (Uma Thurman).

Much of the humor is dependent upon uncannily intelligent dialogue under strange circumstances. Again, Jules gets great laughs from his way of dealing with people he’s about the kill, or in the final scene, the way he handles the robbers in the restaurant. “Point the gun at me,” he helpfully tells the woman who has aimed her gun at Vincent. He quotes the Bible again, as he says he always does before killing someone.

We also hear the ‘distant’ irony of characters contradicting themselves. In the first segment Vincent says he never watches television while in the third segment he vividly describes a show he’s seen. Jules makes much ado to the young men he kills in the first scene that Marsellus is not to be fucked by anyone but his wife, but later he is raped by the hillbillies who tie up him and Butch. It’s also interesting that two of the scenes show Vincent bringing an ugly situation into the world of more law-abiding people: bringing the OD’d Mia to Lance (who at least isn’t a killer), and bringing Marvin’s body to Jimmie’s).

Even in the first scene we are given comedy of manners: consider the casual attitudes of Vincent and Jules as they calmly take the elevator en route to a multiple hit, debating whether a foot massage is a sexual act worthy of the Marsellus’ wrath. Their casualness is a source of humor later on, when they don’t seem to mind hanging around the scene of a hit to discuss whether or not it was a miracle they weren’t hit by bullets (you would think they would immediately leave the crime scene). Perhaps Jules’ belief in miracles is the reason he ultimately survives while Vincent, a skeptic dies.

Pulp Fiction’s Structure

The structure of the three stories is also handled effectively. For the final scene we return to the original diner setting with a different perspective, knowing the diner will be robbed and that Jules and Vincent will be in the scene; this gives us a certain satisfaction. We like seeing Jules give Pumpkin and Honey Bunny a surprise, since they were the ones who violated another unwritten rule by robbing a diner.

But the structure also works nicely because we get to see the rest of Jules and Vincent’s morning. Because Vincent dies in segment two, we get to see him alive again and get that cinematic feeling about the preciousness of life, or the eeriness of knowing he’ll die—without having to resort to prequels or a final Butch Cassidy freeze-frame, or highlights of the person’s life being flashed at us during the closing credits, as in other movies. We are glad to see Vincent alive again. Another reason the violence is so well handled and so effective is because we see the character living for a while (and talking) before he dies, rather than just being a callous stickman who dies as in so many movies.

Or again, a virtue of the structure—that Vincent is killed at the end of segment two rather than later—is that as moviegoers we know that characters we like (even bad guy characters, like Butch Cassidy and Sundance) die at the end of the movie, so we are somewhat shocked by Vincent’s death. If he died at the end of the movie it wouldn’t have the same effect.

Although we are shown interesting characters in extreme scenes (struggling for life, etc.) the characters remain superficial. Maybe this criticism is preempted by titling the movie “Pulp Fiction”; it’s not supposed to be deep. But we don’t know how these characters got this way (resorting to being hit men, or drug-users, fight-fixers, etc.). We are only given an all-pervasive cynicism. Perhaps these gaps are filled in by our imaginations: we’ve seen their stories in other films about similar characters, and those movies would have taken an unwanted moral theme about their decline in immorality and the sadness of it all.

But even if it doesn’t detract from the film, in that this movie is not a psychological study, but ultimately…what is it? A black comedy, with touches of the surreal, such as The Gimp, the odd black-clad creature unleashed for the homosexual rape; or Jody’s (Roseanne Arquette) fascination with the needle in the heart—and her tattoos and rings all over her body.

It’s amazing how completely free from a moral tone this movie is. Everything is just treated in blasé manner where consequences are strictly legal ones or death. No one seems to fear the police at all. When Mia OD’s, there is not even a doctor figure (such as in Wilder’s The Apartment (1960)) to come in lamenting about physical self-destruction. The accidental shooting of Marvin in the car is gratuitous even for the characters; it is simply another problem they have to deal with, such as changing their clothes. They even call in Wolf to deal with it instead.

It is funny that The Wolf, this “expert problem solver,” who is after all so cool, just does the obvious things which the hit men should have figured out for themselves: clean off the car and themselves.

There are only a few touches of an outside, non-superficial presence in the characters’ lives. Butch’s girl laments that what is pleasing to the eye and pleasing to the touch do not agree (but again: Butch has no lament at all for killing what turns out to be several people in his segment; he is even asked about this (how he feels about killing a man) point blank by the taxi driver and says no, it doesn’t bother him).

Jules shows signs of spiritual concern but this is probably only introduced for its ironic effect; there is little hint that Tarantino is offering Jules’ sentiments as a moral for his film.

A virtue of sticking with the immediate present of the scenes, and the circular structure is that the movie suggests a much larger fictional world than it actually covers. We want to see more of Mia, Marsellus, Jules, and even Lance and Jody. Perhaps a prequel could be used to bring back the Vincent character; why did he spend three years in Amsterdam? But Tarantino may have a resistance to prequels and sequels.

#

All the little touches mentioned (and others) show that this is a thoughtful well-made film. But it has no moral. It is entertainment and a commentary about characters we’ve seen in other movies. The movie depends on its “effects”—the violence and threat of violence, the articulateness of its underworld characters, and its structure. Also, that there is such a good cast in small roles. It’s fun to see Keitel, Stoltz, Arquette, Willis, Travolta, Tarantino, and Samuel T. Jackson, and others.

On a critical, aesthetic level I don’t know what to say about this film in the end. It is effective, entertaining, funny, powerful in scenes (though not cumulatively). But it teaches us nothing. Pulp Fiction gives us violence in broad daylight, hip dialogue and circular structure.

Dan Geddes