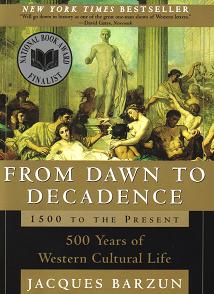

From Dawn To Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life

by Jacques Barzun

Review By Dan Geddes

5 January 2001

For most of its 800 pages From Dawn To Decadence is a triumph of historical survey. Barzun treats countless historical developments with grace and originality, offering new interpretations of developments of the modern era such as Puritanism, The French Revolution, and Romanticism. Barzun’s erudition is astonishing and his writing entertaining throughout the work. When finished the book can also serve as an historical reference, as Barzun’s entries on historical personages often feature a depth not found in plain encyclopedias.

The great flaw in the work is Barzun’s rather high-handed belief that no new cultural developments of merit have occurred in the West since “The Cubist Decade” (1905-1914). Although the 1920s was a time of cultural fecundity, Barzun rightly notes that most of the developments had occurred before World War I, but did not achieve popular recognition until after the war. For Barzun, art since that time has largely been “anti-art,” characterized by abstraction of technique rather than powerful treatment of suggestive subjects. Philosophy and literature have been bankrupt as well, as the only (!) writer since 1950 Barzun finds worthy of mention is Ortega y Gasset. Only a few works after 1920 are treated.

While I believe Barzun is right to see our time as one of cultural decline his summary judgment leads one to the suspicion that Barzun has not experienced the art of his time (a nonagenarian, he began his cultural studies in the 1920s). Certainly the film has emerged as a powerful art form; and the Twentieth Century also produced some poetry and novels of lasting value as well. Perhaps Barzun should have ended his survey around 1920, and omitted his last two chapters, “Embracing The Absurd” and “Demotic Life and Times”, which are eulogies to Western Culture, and not the grand survey that is the rest of his work.

Barzun traces such key cultural developments as primitivism, emancipation, self-consciousness, and abstraction from their beginnings in the 16th century through the present. Barzun shows us that historically there are no new things under the sun, as most historical events have distant precursor. Originality itself is a modern notion.

For Barzun as for many historians, the key “revolutions” were the Protestant Reformation, The English Civil War, and the French and Russian Revolutions. Each of these gave “culture a new face.” But the dates of these events do not represent walls so much as signposts, as cultural history is always a network of growth rather than a chain of causality.

Barzun himself refrains from formulating any general conception of history. He believes history is strongest as literary narrative, and is dubious of the attempts at a philosophy of history, which he feels distort by reducing the march of history to a single cause.

The joy of From Dawn to Decadence lies in Barzun’s insights throughout the text. Barzun debunks many historical myths. For example, the 16th century conception of salvation meant resurrection of the flesh, rather than the immortality of the soul. The Puritans were not entirely sexually repressive, as they admitted the practice of young people “bundling” together on cold nights; but marriage was obligatory after bundlings that resulted in pregnancies. Max Weber’s idea about the connection between Protestantism and the rise of capitalism do not stand when the facts are considered: capitalism predated Protestantism, banking thrived in Catholic Italy, etc.

Barzun’s sketches of historical personages feature striking details and understanding. He also tries to rescue certain little known figures from obscurity.

As much as From Dawn to Decadence can be enjoyed reading straight through, I will also return to it for reference. Its features useful typographic conventions, such as the use of SmallCaps for themes such as primitivism, in-line references to other pages discussing related topics, index of personages.

I guess I find it a shame that such a masterly cultural historian can find so little of value in the entire 20th century. Can Barzun be right? Are 20th century works weaker than their predecessors by an order of magnitude?

5 January 2001

See also: Book reviews and criticism