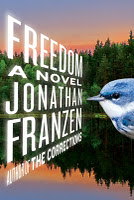

Freedom

by Jonathan Franzen

Review by Dan Geddes

Summary: Franzen solidifies his reputation with a worthy follow-up to The Corrections.

Note: This review contains spoilers and is intended to be read only after you have read the book.

Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom fully deserves the attention that the media has lavished upon it during its current season of publication. Franzen has delivered a great social novel with uncanny insight into our (increasingly digitized) social mores. It features sympathetic and believably flawed characters, and enough social satire to satisfy nearly anyone. In Freedom, the main characters seem so real and alive that they could just walk off the page.

Patty, the former college basketball star turned housewife, is smart, resourceful, and genuinely well-meaning. As a college girl, she rejects her affluent New York suburban upbringing by going to a Minnesota state university against the wishes of her parents. As a college basketball player, she is hungry for the appreciation and even admiration that she never received from her own busy, professional parents. She gets it from some of the wrong people, including Eliza, the English major, drug-experimenting admirer of Patty, who creates an obsessive about Patty’s accomplishments, and later even fakes having leukemia. Through Eliza she meets Richard Katz, an attractive rock star type. Patty is smitten with him. Through Richard she meets Walter, a super nice and “worthy” but not so attractive guy (whom she marries after her Richard fail to hook up).

Clearly, Franzen has thought deeply about these characters. I really cared for the principal characters of Freedom, especially Walter and Patty, even more than for the principal characters of The Corrections (where I didn’t care so much for Chip and Gary as individuals, as much as I enjoyed reading about their problems). Patty and Walter have a good marriage, but an unexciting one, including sexually (for Patty at least). Back in college she had been attracted to Walter’s best friend, Richard, yet they never connected sexually. Richard didn’t want to betray his friend, and thought that Patty was the one woman who was actually worthy of Walter. Patty was disappointed, but instinctively returned to Walter and finally consummated their heretofore platonic relationship.

Franzen has strongly portrayed Patty’s attitudes, her intelligence, sarcasm, and depression. She is totally believable, and her dialogue dead-on accurate. I had difficulty seeing her physically. She’s tall and pretty, but I somehow never imagined her appearance clearly. This is probably deliberate.

Three of the early chapters are presented as Patty’s own writing, as an autobiography (entitled “Mistakes Were Made”) that her therapist suggested that she write. Patty writes a lot like Jonathan Franzen; not just the style, but also the types of insights she makes. The dialogue she relates is believable, but the descriptions are not quite in her voice. So I didn’t believe her autobiography to be the text that Patty (admittedly herself a fictional creation) would produce verbatim. However, it still works for me as an approximation of her voice: what she would choose to tell, in what order, what was said, and with what attitude. But the actual voice of the autobiography as a whole, the diction, is still too clearly Franzen’s.

I imagined Walter more clearly (easily imagining the red face of a distant acquaintance). Walter is such a salt-of-the-earth guy that it’s impossible not to like him (as a reader). We can easily believe how his relationships with his family (and Richard, his surrogate brother) would develop as they do. Information about Walter is fairly scant early on, so we have a lot of curiosity about him. His scandal is mentioned in the first sentence yet it is still not clearly identified or introduced into the current action of the story until the second half. So we wonder just how super nice Walter ultimately will be scandalized.

Richard Katz is Walter’s best friend from college, a guitar player for whom Walter and Patty were the last “normal people” to become his friends before he began to live permanently in other-than-normal middle-class circumstances. Richard is very confident sexually, a proud womanizer. Richard and Patty are mutually attracted, but Richard has “integrity,” and cannot betray Walter—at first. Richard is smart and grungy; he is easy to underestimate. But he is no nihilist; he has his own moral code. And he really respects Walter, as a hard-working responsible guy with his own idealism.

The Walter-Richard friendship illustrates contrasting male types who are nevertheless drawn to each other. There is an “opposites attract” aspect to their relationship. Their competitiveness drives the key changes in their lives, such as Walter quitting his nature conservancy job for a more high-profile, world-changing role as Executive Director of the Cerulean Mountain Trust. Walter enjoys great professional success, as well as the obvious admiration of his beautiful young assistant, Lalitha, who forms the third angle of the Patty-Walter-Lalitha love triangle.[1]

The Walter-Patty-Richard triangle showcases how pride and competitiveness drive so much behavior, though not always in our best interests. Walter and Richard have a competitive friendship, where it can be difficult to see who is “winning,” partially because the rules of the game keep changing. Richard, the confident womanizer, can often seem like he is winning. Yet Walter’s industry, marriage to Patty, and gentrified family life, also seems like a winning hand compared to Richard’s comparative poverty. This is why Patty’s betrayal of Walter with Richard so enrages the otherwise understanding husband. Richard’s cuckolding of Walter clearly gives him the edge.

Patty is also extremely competitive, first with her sisters growing up and later as a basketball player. When her career is over, her tremendous energy goes into fixing up their house and raising her family. But after the kids have left home (Joey at only sixteen to move in with his girlfriend next door), she has an empty Victorian house and no real outlet for her energies. She becomes depressed and starts drinking too much wine. Her desire to be good enough to attract Richard helps drive her to seduce him.

The Walter-Patty-Richard triangle would be enough for a great novel on its own, but Franzen adds another dimension to the novel by including the story of the Joey-Connie-Jenna triangle.

Joey is very competitive with his father, but “corrects” his liberal parents by becoming a Republican (at least in sensibility). He tries to enrich himself working for a corrupt Iraq War subcontractor, selling old trucks and spare parts to the US Army. Through his friend Jonathan, and his beautiful sister, Jenna, Joey develops a sudden interest in his Jewish heritage (Patty’s mother, Joyce, is Jewish, but has always underplayed the fact, much like Enid in The Corrections). Joey remains in favor of the Iraq War, and seeks to profit from it, while Walter is morally outraged by both the war and his son’s attitude toward it.

Joey also finds himself still attached to his high school sweetheart, Connie. Patty can never forgive Connie for seducing her teenage son, even to the point where he moves in with her and low-brow parents at the age of 16. Connie is a bit creepy, and Joey is planning to slowly break away from her after he moves east to go to the University of Virginia. But through his roommate, Jonathan, he meets Jenna, the most beautiful girl he has ever seen, and he resolves on a long-term strategy to win her spoiled little heart. He is in love with both of them, and watching him try to hold his life together under all that pressure is nearly as engaging as the middle-aged love triangle of Walter-Patty-Richard.

#

Franzen creates a powerful spell over us by really making us feel what it’s like to live inside the skulls of the principal characters. The technique is to describe each character’s view on his or her situation with the kinds of words or metaphors they would use to describe it (without any attempt to render the actual stream-of-consciousness verbiage running through their brains). Richard might use musical or sexual metaphors; Patty, basketball or athletic ones; Walter environmental; Joey, monetary.

With The Corrections, Franzen drew back from the brink of becoming a little-read, post-modern literary writer (as he might have seemed destined after his first two novels) and found his own voice in literary realism. He has found a structure which he is comfortable working with. Much like The Corrections, Freedom is a family chronicle with a large section told from the perspective of (though not the actual the narrative voice of) each of the principal characters. The short, first part of Freedom (“Good Neighbors”) is told from the point-of-view of the Berglund family’s neighbors in St. Paul. Then in subsequent sections we zoom in and see things from the perspective of Berglund family members in turn (Patty, Walter, Joey, and Richard (Walter’s surrogate brother), and, not so much, Jessica).

This structure really works for Franzen here, just as in The Corrections. For each main character, he logically includes much of their back story in his or her designated part. This structure creates a lot of dramatic irony as the characters have incomplete knowledge of other characters’ actions and motives that have already been told to the reader. It is also a much smoother construction than novels that shift between first person and third person voice, or between different first person voices. (In Freedom, even when Patty writes a memoir on the advice of her therapist, she does so in third person.) Thus, Freedom is never told from the point-of-view of an objective narrator, but always through the eyes of one of the characters. In principle, this means that any viewpoints expressed are those of a character, rather than the narrator. This means that any viewpoints expressed, are those of the narrator, rather than Franzen. Thus, Walter’s attitudes about overpopulation and endangered species are his, rather than Franzen’s. The descriptions always contain the word choices and value judgments of one of the characters, not necessarily Franzen’s own.

This focus on the characters within a family makes Franzen’s work far more accessible to mass audiences than, for example, the works of Thomas Pynchon, one of Franzen’s influences. Pynchon certainly writes social novels; his works are nothing if not major societal criticisms. Yet Pynchon has too often undermined his own numerous triumphs by torpedoing too many of his characters; by introducing so many characters who are pointless extras—literally names on the page—good for a laugh or two; by deliberate making the reader aware that the characters are in fact just the artificial, literary creations of Thomas Pynchon. Pynchon is truly a self-conscious novelist; Franzen may have the same gene, but he is fighting mightily against it, and against drawing too much attention to his idiosyncrasies.

A chief reason for his success is maintaining a balance between irony and compassion. While sometimes we see Franzen putting his characters in hilariously awkward situations, he has enough self-control as a writer to avoid going only for laughs. He likes or even loves his characters, and he wants his readers to do the same. So he is also compassionate enough with them to always treat them as human beings, and not just as cogs in a laugh machine. Thus, while Freedom is a better book, in my opinion, than The Corrections, it doesn’t have as many laugh-out-loud funny parts. Since Franzen is clearly capable of effective literary slapstick, it takes restraint to forego the pleasure of writing really funny (if perhaps slightly contrived) situations in order to avoid sacrificing the realism of the main characters.

Freedom is what great, topical fiction has always been like, and one reason why fiction used to be far more relevant to the societal conversation than today. Far too much quality fiction or literary fiction since the 1960s has remained largely irrelevant (almost as irrelevant as poetry) to the societal dialogue for all the well-known reasons: deliberate obscurity, authorial self-indulgence, and obvious elitism. Just as so much twentieth century art became non-representational, so did so much late twentieth century “literary” fiction become non-representational of the societies they were supposed to depict (a generalization to be sure). A navel-gazing obsession with literary techniques has obscured the more basic mission to write a compelling topical, story stocked with believable characters.

I recently read a passage about the modern concept of freedom from Franzen’s friend, the late David Foster Wallace. It could serve as an epigraph to Franzen’s Freedom:

But of course there are all different kinds of freedom, and the kind that is most precious you will not hear much talked about in the great outside world of winning and achieving and displaying. The really important kind of freedom involves attention, and awareness, and discipline, and effort, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them, over and over, in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day. That is real freedom. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default-setting, the “rat race” — the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.

Freedom shows characters engaging in precisely this struggle.

This is a book that makes me feel more alive (and to want to write fiction)! Jonathan Franzen has people believing in the novel again.

October 2010

Amsterdam

References

Freedom by Jonathan Franzen, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1st ed.

“David Foster Wallace on Life and Work” Wall Street Journal (Online), accessed 6 October 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122178211966454607.html

[1] I must confess to have been disappointed by Lalitha’s fatal car accident, which temporarily broke the spell of the novel for me. It was almost a John Irving type of crash. It felt as if the story was moving toward its most intense conflict of all: could Walter really choose Lalitha over Patty long-term? He seems to realize it wouldn’t be wise on some level. And yet he is spared this terrible conflict by Lalitha’s sudden death. As painful as it was for him, he is probably better constituted to mourn her for years than to live happily and guiltlessly with her. He seems like the kind of guy who would ultimately have to forgive Patty (as he does). So it doesn’t really make sense for him to be with Lalitha anyway.

See also: Book reviews and criticism